What's So Important About The Pyloric Valve Anyway?

www.youtube.com/watch

Keeping the pyloric valve in play allows for one to drink before, during and after meals. The valve regulates food and liquid differently, allowing liquids to pass while keeping solids to digest further into chyme before passing into the intestines.

While I'm eating, I AM LIMITED to how much I can drink because it is food I want to fill my belly with. I usually consume about 8-10 oz of fluids during a meal. But after dinner is a different story. I love having a large cup of hot tea every evening following my meal.

I am reliant on my pylorus knowing the difference between a steak and a cup of chamomile tea.

http://www.aic.cuhk.edu.hk/web8/gastric_emptying.htm

Gastric emptying

Claudia Cheng

updated in August 2006

Introduction

Stomach emptying is a coordinated function by intense peristaltic contractions in the antrum. At the same time, the emptying is opposed by varying degrees of resistance to passage of chyme at the pylorus. Rate depends on pressure generated by antrum against pylorus resistance. Chyme = food in stomach which has been thoroughly mixed with stomach secretions

Factors affecting stomach empyting

- Promote

§ Gastric volume

o Increased food volume in stomach promotes increased emptying

o Antral distension stimulates vasovagal excitatory reflexes leading to increased antral pump activity

§ Liquid vs solid food

o Clear fluids are empty rapidly (T1/2 » 30 minutes). Solids stay in stomach longer (T1/2 » 1-2 hours)

o Pylorus is open enough for H2O/fluids to empty with ease. Constriction of the pyloric sphincter to solids until chyme is broken down into small particles and mixed to almost fluid consistency

§ Types of food

o Protein empties fastest, followed by carbohydrates. Fats take longest to empty

o Note: high protein food especially meat stimulate release of gastrin from antral mucosa

§ Hormonal factors

o Gastrin has mild to moderate stimulatory effects on motor functions in the body of the stomach. Enhances activity of pyloric pump

o Motilin released by epithelium of the small intestine enhances the strength of the migrating motor complex which is a peristaltic wave that begins within the oesophagus and travels thru the whole GIT every 60-90 min during the interdigestive period. Help empty remaining food in stomach

§ Neural

o Parasympathetic innervation (via vagus) stimulates motility

o Local myenteric reflex

§ Drugs

o Prokinetics eg cisapride, erythromycin metoclopramide

- Inhibit

§ Duodenal distension

o Results in inhibitory enterogastic reflexes

o Slow or even stop stomach emptying if the volume of chyme in the duodenum becomes too much

§ Osmolarity of chyme

o Iso-osmotic gastric contents empty faster than hyper or hypo-osmotic contents due to feedback inhibition produced by duodenal chemoreceptors (hyper more inhibitory than hypo)

§ Types of food

o Fat and protein breakdown products in the small intestine inhibits gastric emptying

§ Acid

o pH of chyme in the small intestine of < 3.5-4 will activate reflexes to inhibit stomach emptying until duodenal chyme can be neutralized by pancreatic and other secretions

§ Temperature

o Cold liquid (40C) empty more slowly

§ Hormones

o Cholecystokinin released from duodenum in response to breakdown products of fat and protein digestion. Blocks the stimulatory effects of gastrin on the antral smooth muscle

o Secretin released from the duodenum in response to acid, has a direct inhibitory effect on the gastric smooth muscles

o Others eg somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), gastic inhibitory peptide (GIP)

§ Neural

o Sympathetic nerves (via the celiac plexus) inhibits motility

§ Patient factors

o Pregnancy delays gastric emptying (progesterone)

o Anxiety delays gastric emptying

o Pain

o Elderly

o Disease states eg diabetes mellitus (autonomic neuropathy), post-operative bowel surgery with resultant ileus, high intra-abdominal pressure

§ Drugs eg. opioids

§ Mechanical eg pyloric stenosis

?Claudia Cheng August 2006

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/484656/pylorus?anchor=ref237588

pylorus,

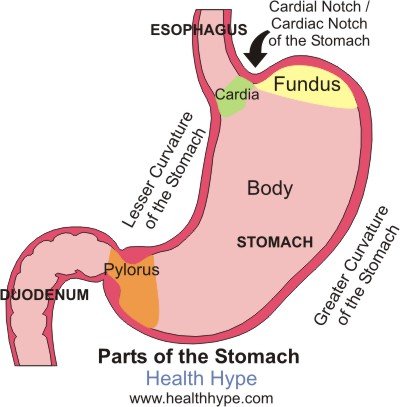

cone-shaped constriction in the gastrointestinal tract that demarcates the end of the stomach and the beginning of the small intestine. The main functions of the pylorus are to prevent intestinal contents from reentering the stomach when the small intestine contracts and to limit the passage of large food particles or undigested material into the intestine.

The internal surface of the pylorus is covered with a mucous-membrane lining that secretes gastric juices. Beneath the lining, circular muscletissue allows the pyloric sphincter to open or close, permitting food to pass or be retained.

A normal functioning stomach.....

http://www.healthhype.com/normal-gastric-stomach-emptying.html

What is gastric emptying?

Gastric emptying is the process by which the stomach empties its contents into the duodenum of the small intestine for further digestion of food and absorption of nutrients. While this may seem like a simple process, it is carefully coordinated so as not to overwhelm the duodenum with large amounts of partially digested food mixed with the acidic gastric secretions, which is collectively known as chyme.

Ask a Doctor Online Now.

How does gastric emptying work?

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ. When food enters the stomach, it is churned by the stomach contractions (peristalsis) with gastric secretions (refer to Gastric Acid Secretion) and this allows for both mechanical and chemical digestion. Most of this churning occurs within the body of the stomach where the muscle contractions are weak.

The contractions lower down the stomach, near the pylorus, are more intense. This pushes the more fluid chyme through the pylorus while undigested food particles are forced higher up into the stomach for further breakdown. These stronger peristaltic waves that occur near the pylorus propel the fluid chyme through the pylorus into the duodenum in a pump-like action. This is referred to as the ‘pyloric pump‘.

The distal part of pylorus has a thick muscular wall arranged in a circular manner which remains contracted in a normal state. This is known as the pyloric sphincter. Even though it is contracted, the sphincter is not totally closed and there is gap which allows fluids like water or chyme to move through into the duodenum but prevents the movement of larger food particles.

What promotes or inhibits gastric emptying?

The vagus nerve is mainly responsible for parasympathetic stimulation to the stomach. This increases peristalsis and opens the pyloric sphincter. Sympathetic stimulation via the celiac plexus inhibits peristalsis and the opening of the sphincter. This is influenced by brain stem as well as stimuli from the sensory nerve endings in the gastric epithelium. Refer to Stomach Nerves for more information on the stomach nerve supply.

.jpg)

And here is an image of the VSG, which is also the restrictive component of the BPD/DS. Note the Pylorus has been left in tact.

www.obesityhelp.com

Duodenal Switch (DS) |

|

|

|

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/dumping-syndrome/DS00715/DSECTION=causes

Causes

By Mayo Clinic staff |

Stomach and pyloric valve |

In dumping syndrome, food and gastric juices from your stomach move to your small intestine in an unregulated, abnormally fast manner. This accelerated process is most often related to changes in your stomach associated with surgery. For example, when the opening (pylorus) between your stomach and the first portion of the small intestine (duodenum) has been damaged or removed during an operation, dumping syndrome may develop.

Dumping syndrome may occur at least mildly in one-quarter to one-half of people who have had gastric bypass surgery. It develops most commonly within weeks after surgery, or as soon as you return to your normal diet. The more stomach removed or bypassed, the more likely that the condition will be severe. It sometimes becomes a chronic disorder.

Gastrointestinal hormones also are believed to play a role in this rapid dumping process.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173594-overview

Background

The stomach serves as the receptive and storage site of ingested food. The primary functions of the stomach are to act as a reservoir, to initiate the digestive process, and to release its contents downstream into the duodenum in a controlled fashion. The capacity of the stomach in adults is approximately 1.5-2 liters, and its location in the abdomen allows for considerable distensibility. Gastric motility is regulated by the enteric nervous system, which is influenced by extrinsic innervation and by circulating hormones. Alterations in gastric anatomy after surgery or interference in its extrinsic innervation (vagotomy) may have profound effects on gastric emptying. These effects, for convenience, have been termed postgastrectomy syndromes.

Postgastrectomy syndromes include small capacity, dumping, bile gastritis, afferent loop syndrome, efferent loop syndrome, anemia, and metabolic bone disease. Postgastrectomy syndromes are iatrogenic conditions which may arise from partial gastrectomies, independent of whether the gastric surgery was initially done for peptic ulcer disease, cancer, or for weight loss (bariatric). The surgical procedures include Billroth-I, Billroth-II, and Roux-en-Y.1

Pathophysiology

Dumping is the effect of altered gastric reservoir function, and abdominal postoperative gastric motor function.2The early dumping syndrome and reflux gastritis are less frequent when segmented gastrectomy rather than distal gastrectomy is performed for early gastric cancer.3 In persons with long segment Barrett esophagus treated with a truncal vagotomy, partial gastrectomy, plus Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, 41% developed dumping within the first 6 months after surgery, but severe dumping is rare (5% of cases).4

The dumping syndrome occurs in 45% of persons who are malnourished and who have had a partial or complete gastrectomy.5 The late dumping syndrome is suspected in the person who has symptoms of hypoglycemia in the setting of previous gastric surgery, and this late dumping can be proven with an oral glucose tolerance test (hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia), as well as gastric emptying scintigraphy that shows the abnormal pattern of initially delayed and then accelerated gastric emptying.6

Clinically significant dumping syndrome occurs in approximately 10% of patients after any type of gastric surgery. Dumping syndrome has characteristic alimentary and systemic manifestations. It is the most common and often disabling postprandial syndrome observed after a variety of gastric surgical procedures, such as vagotomy, pyloroplasty, gastrojejunostomy, and laparoscopic Nissan fundoplication. Dumping syndrome can be separated into early and late forms, depending on the occurrence of symptoms in relation to the time elapsed after a meal. Both forms occur because of rapid delivery of large amounts of osmotically active solids and liquids into the duodenum. Dumping syndrome is the direct result of alterations in the storage function of the stomach and/or the pyloric emptying mechanism.

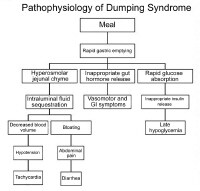

Pathophysiology of dumping syndrome.

The accommodation response and the phasic contractility of the stomach in response to distention are abolished after vagotomy or partial gastric resection.7 This probably accounts for the immediate transfer of ingested contents into the duodenum. Hertz made the association between postprandial symptoms and gastroenterostomy in 1913.8 Hertz stated that the condition was due to "too rapid drainage of the stomach." Mix first used the term "dumping" in 1922 after observing radiographically the presence of rapid gastric emptying in patients with vasomotor and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

The severity of dumping syndrome is proportional to the rate of gastric emptying. Postprandially, the function of the body of the stomach is to store food and to allow the initial chemical digestion by acid and proteases before transferring food to the gastric antrum. In the antrum, high-amplitude contractions triturate the solids, reducing the particle size to 1-2 mm. Once solids have been reduced to this desired size, they are able to pass through the pylorus. An intact pylorus prevents the passage of larger particles into the duodenum. Gastric emptying is controlled by fundic tone, antropyloric mechanisms, and duodenal feedback. Gastric surgery alters each of these mechanisms in several ways.

Gastric resection reduces the fundic reservoir, thereby reducing the stomach's receptiveness (accommodation) to a meal. Vagotomy increases gastric tone, similarly limiting accommodation. An operation in which the pylorus is removed, bypassed, or destroyed increases the rate of gastric emptying. Duodenal feedback inhibition of gastric emptying is lost after a bypass procedure, such as gastrojejunostomy. Accelerated gastric emptying of liquids is a characteristic feature and a critical step in the pathogenesis of dumping syndrome. Gastric mucosal function is altered by surgery, and acid and enzymatic secretions are decreased. Also, hormonal secretions that sustain the gastric phase of digestion are affected adversely. All these factors interplay in the pathophysiology of dumping syndrome.

app.barisecure.com/resources/NIWLS_NMD.doc

Dumping Syndrome

The two types of Dumping Syndrome are alternately discussed as a benefit or side effect of RNY. Early Dumping typically occurs 30 to 60 minutes after eating high concentrations of sugars or overeating. Because the pylorus is eliminated with RNY, the pouch can empty rapidly into the jejunum (the duodenum is bypassed). For reasons possibly connected to changes in blood flow and/or post-prandial release of gut peptides[i], patients experience a sudden and very unpleasant onset of symptoms including cramps, nausea and vomiting, explosive diarrhea, and dizziness, tachycardia, decreased blood pressure, and flushing. Early dumping is common in the first year after RNY and is promoted as behavior modification, since it is a very unpleasant response to eating sweets.

Late Dumping occurs one to three hours after eating, also in response to sugars or refined carbohydrates. Symptoms of severe hypoglycemia (sweating, tremors, exhaustion, decreased consciousness, fainting, hunger and sugar cravings) result from the efficiency of the small bowel in absorption of simple carbohydrate. This, in turn, leads to a hyperinsulinemic response[ii].

Dumping syndrome is reported in as many as 50[iii] to 70 percent of RNY patients.[iv] Dietary recommendations include reduction of sugar and refined carbohydrate, avoidance of fluids at meal times (to slow gastric emptying), and consumption of protein-rich meals[v]. The somatostatin analog, octreotide, can be used to control symptoms[vi] in extreme or refractory cases.

5 Carvajal SH, Mulvihill SJ. Postgastrectomy syndromes: dumping and diarrhea. Gastroenterol ClinNorth Am. 1994;23(2):261–279.

6Holdsworth CD, Turner D, McIntyre N: Pathophysiology of post-gastrectomy hypoglycaemia. Br Med J 1969 Nov 1; 4(678): 257-9

7Sugerman HJ, Starkey JV, Birkenhauer R. A randomized prospective trial of gastric bypass versus vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity and their effects on sweets versus non-sweets eaters.Ann Surg. 1987;205(6):613–624.

8Pories WJ, Caro JF, Flickinger EG, Meelheim HD, Swanson MS. The control of diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) in the morbidly obese with the Greenville Gastric Bypass. Ann Surg. 1987;206(3):316–323.

9 Elliot K. Nutritional considerations after bariatric surgery. Crit Care Nurs Quart. 2003;26(2):133-138.

10 Gray JL, Debas HT, Mulvihill SJ: Control of dumping symptoms by somatostatin analogue in patients after gastric surgery. Arch Surg 1991 Oct; 126(10): 1231-5; discussion 1235-6.

http://cine-med.com/index.php?nav=surgery&subnav=acs&id=ACS- 2781

We believe that rapid emptying of the non valved gastric bypass leads to reactive hypoglycemia and weight gain after the first year. It is our contention that preservation of the pyloric valve, the thinest area of the gi tract, will provide for better long term outcomes. This operation does not need to be severely malabsorbtive. We conclude that pyloric preservation will become a standard priciple in bariatric surgery in years to come.

Here is a full article link titled:

IS IT TIME TO BYPASS THE BYPASS?

SHOULD THE PYLORIC PRESERVATION

BECOME AN IMPORTANT PRINCIPLE

IN BARIATRIC SURGERY?

www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/matrix/bt_supp0609/index.php

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00998374

Comparison Between Pyloric Preserving and Non-Pyloric Preserving Bariatric Surgery With Glucose Challenge This study is currently recruiting participants. Study NCT00998374 Information provided by Covidien First Received: October 15, 2009 Last Updated: November 17, 2010 History of Changes

New Data on Weight Gain Following Bariatric Surgery

Gastric bypass surgery has long been considered the gold standard for weight loss. However, recent studies have revealed that this particular operation can lead to potential weight gain years later. Lenox Hill Hospital’s Chief of Bariatric Surgery, Mitchell Roslin, MD, was the principal investigator of the Restore Trial – a national ten center study investigating whether an endoscopic suturing procedure to reduce the size of the opening between the gastric pouch of the bypass and the intestine could be used to control weight gain in patients following gastric bypass surgery. The concept for the trial originated when Dr. Roslin noticed a pattern of weight gain with a significant number of his patients, years following gastric bypass surgery. While many patients could still eat less than before the surgery and become full faster, they would rapidly become hungry and feel light headed, especially after consuming simple carbohydrates, which stimulate insulin production.

The results of the Restore Trial, which were published in January 2011, did not confirm the original hypothesis – there was no statistical advantage for those treated with suturing. However, they revealed something even more important. The data gathered during the trial and the subsequent glucose tolerance testing verified that patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery and regained weight were highly likely to have reactive hypoglycemia, a condition in which blood glucose drops below the normal level, one to two hours after ingesting a meal high in carbs. Dr. Roslin and his colleagues theorized that the rapid rise in blood sugar – followed by a swift exaggerated plunge – was caused by the absence of the pyloric valve, a heavy ring of muscle that regulates the rate at which food is released from the stomach into the small intestine. The removal of the pyloric valve during gastric bypass surgery causes changes in glucose regulation that lead to inter-meal hunger, impulse-snacking, and consequent weight regain.

Dr. Roslin and his team decided to investigate whether two other bariatric procedures that preserve the pyloric valve – sleeve gastrectomy and duodenal switch – would lead to better glucose regulation, thus suppressing weight regain. The preliminary data of this current study shows that all three operations initially reduce fasting insulin and glucose. However, when sugar and simple carbs are consumed, gastric bypass patients have a 20-fold increase in insulin production at six months, compared to a 4-fold increase in patients who have undergone either a sleeve gastrectomy or a duodenal switch procedure. The dramatic rise in insulin in gastric bypass patients causes a rapid drop in glucose, promoting hunger and leading to increased food consumption.

“Based on these results, I believe that bariatric procedures that preserve the pyloric valve lead to better physiologic glucose regulation and ultimately more successful long-term maintenance of weight-loss," said Dr. Roslin.

www.nwhsurgicalweightloss.org/default/learn-about-your-condition-and-treatment/pyloric-preservation

Pyloric Preservation

An emerging principle, and something that may become a cornerstone of all bariatric procedures is the concept of preserving the pylorus valve, or “Pyloric Preservation". The pylorus is the valve located at the end of the stomach. It controls the release of the liquid mixture of food that the stomach creates from the stomach into the small intestine.

The body naturally regulates the passage of food, so that food will stay in the stomach for a certain period of time. We believe it’s very important to continue that feeling of “fullness" in between meals. As a result, one of the principle functions of the pyloric valve is to regulate the amount of food products that are released into the small intestine where they are absorbed.

For years, we have performed gastric bypass surgery and hoped that the attachment we made between the new stomach pouch and the intestine would scar and narrow to create a “fixed" outlet. Unfortunately we found that in many patients the outlet enlarges and there’s a rapid passage of food from the pouch into the intestine. When that occurs, patients become hungry shortly after eating.

To combat this, people have used a number of different strategies. Dr. Fobi in California advocates using a silastic band, and created an operation called the Fobi Pouch. Recently, versions of the Fobi pouch have been used, and demonstrate there’s less weight regain than compared to standard gastric bypass.

At NWH, we favor another solution. We believe the body has a natural valve called the pylorus. We’d rather preserve this valve than use something like the silastic band, as we believe this causes another set of variables and can create issues in the future.

There’s a large difference between a natural or biologic valve and a synthetic or silastic/silicon valve. The biologic valve has the ability to relax and close when appropriate or biologically necessary. A mechanical valve does not have the ability to relax, and therefore remains in the same position.

The pyloric valve is the stomach’s version of a sphincter, controlling the release of food. We believe best results will be obtained by preserving this valve in the future. That’s why we advocate two operations which do this. One is the sleeve gastrectomy and the other is the duodenal switch operation. We’ve created a version of this procedure where we create a pouch which is similar in size to the sleeve gastrectomy, preserve the pyloric valve and then do a bypass underneath the pyloric valve, similar in length to the gastric bypass. With this operation, we have seen excellent weight loss without frequent bowel movements, and at present, no greater nutritional deficiencies than we see with gastric bypass surgery.

An improvement of the BPD (it is also referred to as “BPD/DS"). Here again, there is a significant malabsorptive component which acts to maintain weight loss long term. The patient must be closely monitored to guard against severe nutritional deficiencies. This procedure, unlike the BPD, keeps the pyloric valve intact. That is the main difference between the BPD and the DS.

An improvement of the BPD (it is also referred to as “BPD/DS"). Here again, there is a significant malabsorptive component which acts to maintain weight loss long term. The patient must be closely monitored to guard against severe nutritional deficiencies. This procedure, unlike the BPD, keeps the pyloric valve intact. That is the main difference between the BPD and the DS.