Did Someone Say Pyloric Valve?

I am going to copy and paste some info, basically because others can explain it far better than my own incoherent ramblings.

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/484656/pylorus?anchor=ref237588

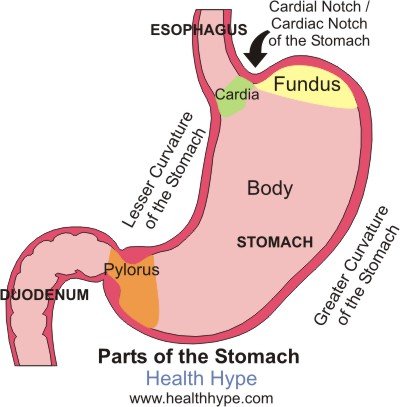

pylorus,

cone-shaped constriction in the gastrointestinal tract that demarcates the end of the stomach and the beginning of the small intestine. The main functions of the pylorus are to prevent intestinal contents from reentering the stomach when the small intestine contracts and to limit the passage of large food particles or undigested material into the intestine.

The internal surface of the pylorus is covered with a mucous-membrane lining that secretes gastric juices. Beneath the lining, circular muscletissue allows the pyloric sphincter to open or close, permitting food to pass or be retained.

A normal functioning stomach.....

http://www.healthhype.com/normal-gastric-stomach-emptying.html

What is gastric emptying?

Gastric emptying is the process by which the stomach empties its contents into the duodenum of the small intestine for further digestion of food and absorption of nutrients. While this may seem like a simple process, it is carefully coordinated so as not to overwhelm the duodenum with large amounts of partially digested food mixed with the acidic gastric secretions, which is collectively known as chyme.

Ask a Doctor Online Now.

How does gastric emptying work?

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ. When food enters the stomach, it is churned by the stomach contractions (peristalsis) with gastric secretions (refer to Gastric Acid Secretion) and this allows for both mechanical and chemical digestion. Most of this churning occurs within the body of the stomach where the muscle contractions are weak.

The contractions lower down the stomach, near the pylorus, are more intense. This pushes the more fluid chyme through the pylorus while undigested food particles are forced higher up into the stomach for further breakdown. These stronger peristaltic waves that occur near the pylorus propel the fluid chyme through the pylorus into the duodenum in a pump-like action. This is referred to as the ‘pyloric pump‘.

The distal part of pylorus has a thick muscular wall arranged in a circular manner which remains contracted in a normal state. This is known as the pyloric sphincter. Even though it is contracted, the sphincter is not totally closed and there is gap which allows fluids like water or chyme to move through into the duodenum but prevents the movement of larger food particles.

What promotes or inhibits gastric emptying?

The vagus nerve is mainly responsible for parasympathetic stimulation to the stomach. This increases peristalsis and opens the pyloric sphincter. Sympathetic stimulation via the celiac plexus inhibits peristalsis and the opening of the sphincter. This is influenced by brain stem as well as stimuli from the sensory nerve endings in the gastric epithelium. Refer to Stomach Nerves for more information on the stomach nerve supply.

.jpg)

And here is an image of the VSG, which is also the restrictive component of the BPD/DS. Note the Pylorus has been left in tact.

www.obesityhelp.com

Duodenal Switch (DS) |

|

|

|

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/dumping-syndrome/DS00715/DSECTION=causes

Causes

By Mayo Clinic staff |

Stomach and pyloric valve |

In dumping syndrome, food and gastric juices from your stomach move to your small intestine in an unregulated, abnormally fast manner. This accelerated process is most often related to changes in your stomach associated with surgery. For example, when the opening (pylorus) between your stomach and the first portion of the small intestine (duodenum) has been damaged or removed during an operation, dumping syndrome may develop.

Dumping syndrome may occur at least mildly in one-quarter to one-half of people who have had gastric bypass surgery. It develops most commonly within weeks after surgery, or as soon as you return to your normal diet. The more stomach removed or bypassed, the more likely that the condition will be severe. It sometimes becomes a chronic disorder.

Gastrointestinal hormones also are believed to play a role in this rapid dumping process.

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/173594-overview

Background

The stomach serves as the receptive and storage site of ingested food. The primary functions of the stomach are to act as a reservoir, to initiate the digestive process, and to release its contents downstream into the duodenum in a controlled fashion. The capacity of the stomach in adults is approximately 1.5-2 liters, and its location in the abdomen allows for considerable distensibility. Gastric motility is regulated by the enteric nervous system, which is influenced by extrinsic innervation and by circulating hormones. Alterations in gastric anatomy after surgery or interference in its extrinsic innervation (vagotomy) may have profound effects on gastric emptying. These effects, for convenience, have been termed postgastrectomy syndromes.

Postgastrectomy syndromes include small capacity, dumping, bile gastritis, afferent loop syndrome, efferent loop syndrome, anemia, and metabolic bone disease. Postgastrectomy syndromes are iatrogenic conditions which may arise from partial gastrectomies, independent of whether the gastric surgery was initially done for peptic ulcer disease, cancer, or for weight loss (bariatric). The surgical procedures include Billroth-I, Billroth-II, and Roux-en-Y.1

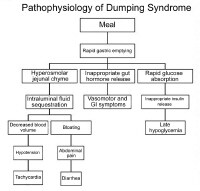

Pathophysiology

Dumping is the effect of altered gastric reservoir function, and abdominal postoperative gastric motor function.2The early dumping syndrome and reflux gastritis are less frequent when segmented gastrectomy rather than distal gastrectomy is performed for early gastric cancer.3 In persons with long segment Barrett esophagus treated with a truncal vagotomy, partial gastrectomy, plus Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, 41% developed dumping within the first 6 months after surgery, but severe dumping is rare (5% of cases).4

The dumping syndrome occurs in 45% of persons who are malnourished and who have had a partial or complete gastrectomy.5 The late dumping syndrome is suspected in the person who has symptoms of hypoglycemia in the setting of previous gastric surgery, and this late dumping can be proven with an oral glucose tolerance test (hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia), as well as gastric emptying scintigraphy that shows the abnormal pattern of initially delayed and then accelerated gastric emptying.6

Clinically significant dumping syndrome occurs in approximately 10% of patients after any type of gastric surgery. Dumping syndrome has characteristic alimentary and systemic manifestations. It is the most common and often disabling postprandial syndrome observed after a variety of gastric surgical procedures, such as vagotomy, pyloroplasty, gastrojejunostomy, and laparoscopic Nissan fundoplication. Dumping syndrome can be separated into early and late forms, depending on the occurrence of symptoms in relation to the time elapsed after a meal. Both forms occur because of rapid delivery of large amounts of osmotically active solids and liquids into the duodenum. Dumping syndrome is the direct result of alterations in the storage function of the stomach and/or the pyloric emptying mechanism.

Pathophysiology of dumping syndrome.

The accommodation response and the phasic contractility of the stomach in response to distention are abolished after vagotomy or partial gastric resection.7 This probably accounts for the immediate transfer of ingested contents into the duodenum. Hertz made the association between postprandial symptoms and gastroenterostomy in 1913.8 Hertz stated that the condition was due to "too rapid drainage of the stomach." Mix first used the term "dumping" in 1922 after observing radiographically the presence of rapid gastric emptying in patients with vasomotor and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms.

The severity of dumping syndrome is proportional to the rate of gastric emptying. Postprandially, the function of the body of the stomach is to store food and to allow the initial chemical digestion by acid and proteases before transferring food to the gastric antrum. In the antrum, high-amplitude contractions triturate the solids, reducing the particle size to 1-2 mm. Once solids have been reduced to this desired size, they are able to pass through the pylorus. An intact pylorus prevents the passage of larger particles into the duodenum. Gastric emptying is controlled by fundic tone, antropyloric mechanisms, and duodenal feedback. Gastric surgery alters each of these mechanisms in several ways.

Gastric resection reduces the fundic reservoir, thereby reducing the stomach's receptiveness (accommodation) to a meal. Vagotomy increases gastric tone, similarly limiting accommodation. An operation in which the pylorus is removed, bypassed, or destroyed increases the rate of gastric emptying. Duodenal feedback inhibition of gastric emptying is lost after a bypass procedure, such as gastrojejunostomy. Accelerated gastric emptying of liquids is a characteristic feature and a critical step in the pathogenesis of dumping syndrome. Gastric mucosal function is altered by surgery, and acid and enzymatic secretions are decreased. Also, hormonal secretions that sustain the gastric phase of digestion are affected adversely. All these factors interplay in the pathophysiology of dumping syndrome.

"Clinically significant dumping syndrome occurs in approximately 10% of patients after any type of gastric surgery."

Evidently, removal of the pyloric valve is not the only cause of dumping. I have VSG and I have mild dumping if I eat sweet fatty foods, like icecream or any rich dessert. Keeps me in check, I'll tell ya that.

Phyllis

"Me agreeing with you doesn't preclude you from being a deviant."

Hala. RNY 5/14/2008; Happy At Goal =HAG

"I can eat or do anything I want to - as long as I am willing to deal with the consequences"

![]()

"Failure is not falling down, It is not getting up once you fell... So pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and start all over again...."

Good luck

Phyllis

"Me agreeing with you doesn't preclude you from being a deviant."

Abnormal glucose tolerance testing following gastric bypass demonstrates reactive hypoglycemia.

Roslin M, Damani T, Oren J, Andrews R, Yatco E, Shah P.

Department of Surgery, Lenox Hill Hospital, 186 East 76th Street, New York, NY, 10021, USA.

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Symptoms of reactive hypoglycemia have been reported by patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery who experience maladaptive eating behavior and weight regain. A 4-h glucose tolerance test (GTT) was used to assess the incidence and extent of hypoglycemia.

METHODS: Thirty-six patients who were at least 6 months postoperative from RYGB were administered a 4-h GTT with measurement of insulin levels. Mean age was 49.4 ± 11.4 years, mean preoperative body mass index (BMI) was 48.8 ± 6.6 kg/m(2), percent excess BMI lost (%EBL) was 62.6 ± 21.6%, mean weight change from nadir weight was 8.2 ± 8.6 kg, and mean follow-up time was 40.5 ± 26.7 months. Twelve patients had diabetes preoperatively.

RESULTS: Thirty-two of 36 patients (89%) had abnormal GTT. Six patients (17%) were identified as diabetic based on GTT. All six of these patients were diabetic preoperatively. Twenty-six patients (72%) had evidence of reactive hypoglycemia at 2 h post glucose load. Within this cohort of 26 patients, 14 had maximum to minimum glucose ratio (MMGR) > 3:1, 5 with a ratio > 4:1. Eleven patients had weight regain greater than 10% of initial weight loss (range 4.9-25.6 kg). Ten of these 11 patients (91%) with weight recidivism showed reactive hypoglycemia.

CONCLUSIONS: Abnormal GTT is a common finding post RYGB. Persistence of diabetes was noted in 50% of patients with diabetes preoperatively. Amongst the nondiabetic patients, reactive hypoglycemia was found to be more common and pronounced than expected. Absence of abnormally high insulin levels does not support nesidioblastosis as an etiology of this hypoglycemia. More than 50% of patients with reactive hypoglycemia had significantly exaggerated MMGR. We believe this may be due to the nonphysiologic transit of food to the small intestine due to lack of a pyloric valve after RYGB. This reactive hypoglycemia may contribute to maladaptive eating behaviors leading to weight regain long term. Our data suggest that GTT is an important part of post-RYGB follow-up and should be incorporated into the routine postoperative screening protocol. Further studies on the impact of pylorus preservation are necessary.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21184112

Ht. 5'2 HW 234/GW 150/LW 128/CW 132 Size 18/20 to a size 4 in 9 months!

An improvement of the BPD (it is also referred to as “BPD/DS"). Here again, there is a significant malabsorptive component which acts to maintain weight loss long term. The patient must be closely monitored to guard against severe nutritional deficiencies. This procedure, unlike the BPD, keeps the pyloric valve intact. That is the main difference between the BPD and the DS.

An improvement of the BPD (it is also referred to as “BPD/DS"). Here again, there is a significant malabsorptive component which acts to maintain weight loss long term. The patient must be closely monitored to guard against severe nutritional deficiencies. This procedure, unlike the BPD, keeps the pyloric valve intact. That is the main difference between the BPD and the DS.