Help, I'm losing my mind!!!!

. Hat flashes all day long, at least 1 every 1/2 hour. Can't sleep at night, I wake at leat 4 to 5 times a night

. Hat flashes all day long, at least 1 every 1/2 hour. Can't sleep at night, I wake at leat 4 to 5 times a night . I'm exhausted and need to know what has worked for some of you. Thank you for taking time to read.

. I'm exhausted and need to know what has worked for some of you. Thank you for taking time to read. Well, I don't really have any info for you, but I just thought I would show some love! I'm really sorry that you are having these crappy hot flashes!

::big hugs::

Hope ya feel better soon!

Love ya,

Heather =)

*~*PROUD OH Support Group Leader*~*

Join SCALE~Second Chance At Life Everyday~Click HERE!

*Discount Codes: NY Conference MarloweNY11*

Jamie Ellis RN MS NPP

100cm proximal Lap RNY 10/9/02 Dr. Singh Albany, NY

320(preop)/163(lowest)/185(current) 5'9'' (lost 45# before surgery)

Plastics 6/9/04 & 11/11/2005 Dr. King www.albanyplasticsurgeons.com

http://www.obesityhelp.com/member/jamiecatlady5/

"Being happy doesn't mean everything's perfect, it just means you've decided to see beyond the imperfections!"

Sounds like time I would seek medical attention for this, either returning to my OBGYN or getting into see a second opinion; wouldn't hurt to confer with bariatric surgeon. Not sure if OBGYN is awware of the possible decrease in absorbtion with hormones in general after WLS, although the patch may bypass that issue.

Professionally when I have seen these issues in people (usually non WLSers) at times antidepressants havehelped many of the symptoms of menopaus, Effexor and Paxil are the 2 I have used with success. Again I can not assess, diagnose or treat over email but just food for thought. Do you see a psychiatric prescriber?

Prozac and Neurontin also have been used....

To Print: Click your browser's PRINT button.

NOTE: To view the article with Web enhancements, go to:

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/471894

----------------------------------------------------

Managing Menopausal Symptoms After the Women's Health Initiative

Barbara Hackley, CNM, MS; Mary Ellen Rousseau, CNM, MS

J Midwifery Womens Health 49(2):87-95, 2004. © 2004 Elsevier Science, Inc.

Posted 03/23/2004

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Until the results of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) were released in July 2002, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) had been thought to be the most effective way to manage unwanted menopausal symptoms and to prevent long-term health problems associated with aging. The results of the WHI, showing that HRT is less beneficial and associated with more risks than previously thought, has complicated the management of unwanted menopausal symptoms. This article discusses the effectiveness of HRT and other modalities used to relieve menopausal symptoms and discusses how to choose an HRT product to match specific menopausal complaints and provide maximum safety.

Introduction

Since the 1980s, increasing numbers of peri- and postmenopausal women have turned to hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for the relief of menopausal symptoms and the prevention of long-term problems associated with aging. In one large national cohort study, 11% of women who became menopausal between 1925 and 1944 had used HRT, compared to 46% of women who became menopausal between 1990 and 1992.[1] More than 46 million prescriptions for Premarin and 22 million prescriptions for Prempro, the most commonly used forms of HRT, were written in the year 2000 alone.[2] However, after the release of the results of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) in 2002, showing that HRT is less beneficial and associated with more risks than previously thought, use of these products declined by more than 30%,[3] reflecting the growing concern over their safety. The WHI findings have complicated the management of unwanted menopausal symptoms. This article reviews the effectiveness of HRT and other modalities used to relieve menopausal symptoms and discusses the choice of HRT products to match specific menopausal complaints and provide maximum safety.

The Evolution of Hormone Replacement Therapy

Synthetic estrogen, developed in the late 1930s, was marketed as estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) for the relief of menopausal symptoms. In the mid 1970s, progesterone was added for use in women with a uterus to prevent the development of endometrial cancer. This combination of estrogen-progesterone became known as HRT. During the 1980s, newer research, based primarily on epidemiological studies, suggested that ERT and HRT might be helpful in preventing many chronic conditions associated with aging such as cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis.[4] Other studies showed positive effects of hormone therapy on cardiovascular risk factors.[5-7] The Nurses Health Study, a large observational cohort study, suggested that postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy reduced cardiovascular disease risk by approximately 50%.[8] Based on these studies, many authorities recommended that all women be counseled about using ERT and HRT for the prevention of chronic disease, in addition to its original use for the relief of menopausal symptoms.

Randomized controlled trials followed. Results from the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Studies (HERS 1 and HERS 2) indicated that HRT provided no protection from cardiovascular disease, at least for the medically complicated women enrolled in these trials. The null effect of the HERS trials shook the foundation on which recommendations for widespread use of estrogen replacement were built.[9,10] In response, the American Heart Association stated that HRT and ERT should not be recommended for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease until future randomized trials confirmed cardiovascular benefit.[11] Critics discounted the results of the HERS data, claiming that the results would be different in healthier populations. Clinicians eagerly awaited the results of the WHI, the first randomized trial to directly address the impact of estrogen plus progestin use on the risk of coronary heart disease in essentially healthy women. The main outcome measures of WHI included both benefits and risks; the main adverse events were invasive breast cancer, stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, hip fracture, and death due to other causes. The combined hormone arm of the study was halted in May 2002 when, after a mean of 5.2 years of estrogen plus progestin use, the overall health risks exceeded benefits.[12] Other arms of the study, including use of estrogen only, calcium plus vitamin D, low-fat diet, and an observational trial, are still ongoing. Findings of the WHI included increased risk of cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, stroke, and pulmonary embolism. Because of these findings, the HRT arm of the study was discontinued despite modest improvements in colorectal cancer risks and osteoporosis (Table 1).

The results of WHI came as a surprise to many in light of three decades of observational data that suggested that HRT provided significant protection against heart disease.[13] Most experts in the field assumed the findings would support estimates obtained from observational studies; therefore, the methodology used in WHI came under great scrutiny and was criticized for several reasons.The women enrolled in the study were older (mean age of 62) and may have been in worse health than women in the general population who commonly start and finish HRT use at much younger ages. This result could have made the findings of the WHI not applicable to younger women. The study also could not determine whether the negative effects on heart disease were from the specific products used in this study; it remains unclear whether the use of different doses, regimens, or methods of administration of HRT would result in the same findings. However, because the study was halted, the FDA has mandated that the labeling for all HRT products be changed to reflect the possible increased risk of heart disease with HRT use. In addition, authorities agree that ERT and HRT should not be used for primary prevention of heart disease and suggest minimizing the length of time these products are used.[14-16] Thus, the consensus appears to be that short-term use of HRT for the relief of menopausal symptoms is appropriate.

Menopausal Relief Measures

HRT regimens are highly effective for the relief of menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are significantly reduced with HRT use,[17] as are other symptoms, such as insomnia[18] and vaginal discomfort.[19] HRT has also been thought to relieve stress incontinence and urinary symptoms,[20] although this association is less well studied than the relationship between HRT and vaginal complaints.

Other choices such as herbs, soy products, and other medications, are available which may help relieve unwanted symptoms of the perimenopause. The effectiveness of these other modalities is not as well researched as HRT and is, in general, based on smaller and fewer well-designed studies. Often these studies lack a long-term placebo arm. Well-designed studies need to include both placebo and treatment arms and be of sufficient duration and size in each arm to be able to measure any attenuation of the placebo effect that occurs over time.[21]

The correct dosage, duration of treatment, and form of alternative products (e.g., soy and herbs) are in dispute, making it difficult to evaluate their effectiveness. Although these products are widely used, randomized controlled studies seem to indicate that although a few may be helpful, many of these products are minimally effective at best. However, because up to 46% of perimenopausal women use complementary therapies,[22] it is important that nurse-midwives understand these options.

Matching Product to Symptom

Just as HRT products differ, so do alternatives such as herbs, nutritional supplements, and lifestyle modifications. Therefore, careful consideration of all the possible options will allow women to choose the best approach(es) for specific complaints.

Hot Flashes

Oral,[23] transdermal,[24] and vaginal ring products[25] have all been shown to reduce the incidence and severity of hot flashes by approximately 80%. Estrogen vaginal creams are marketed for the relief of vaginal atrophy; neither their package inserts nor the medical literature address their impact on vasomotor symptoms. Locally applied vaginal creams have a systemic absorption rate of only about 4% and are, therefore, unlikely to have significant impact on systemic symptoms such as hot flashes.

Although HRT products (except vaginal creams) provide relief from vasomotor symptoms, their effectiveness varies somewhat by dose and specific component. In a review of the literature, Shanafelt concludes that the most important component of HRT regimens for the relief of vasomotor symptoms is estrogen -- with higher doses being more effective than lower ones.[26] Neither the type of progestin -- nor even the addition of a progestin -- seems to significantly influence effectiveness, at least at standard HRT doses.[23,26] However, the addition of a progestin does seem to make a difference when using low-dose estrogen regimens. A recent double-blind randomized trial of various low-dose conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) regimens demonstrated the beneficial effects of adding a progestin to low-dose regimens.[27] More than 2,000 women were randomized into eight different HRT treatment arms comparing placebo with various combinations of conjugated equine estrogen doses ranging from 0.30 mg to 0.625 mg and MPA doses ranging from 1.5 mg to 2.5 mg. Although vasomotor symptoms improved in all treatment groups, women receiving low-dose estrogen-only regimens (containing doses of CEE lower than 0.625 mg) had less improvement than women receiving standard-dose regimens (containing CEE 0.625 mg alone or combined with MPA).[27] However, adding a progestin to a low-dose estrogen regimen raised the effectiveness to the same level provided by the standard regimens.[27]

HRT products show a dose-response curve with HRT formulations containing higher doses of estrogen affording better relief more quickly. However, over time, most lower-dose regimens provide acceptable levels of relief from vasomotor symptoms and may potentially have fewer side effects. In a study of the efficacy and safety of three different dosages of Esclim patches in 196 postmenopausal women, lower doses provided effective, albeit, slightly delayed relief.[24] Significant reductions in symptoms occurred by week 2 for Esclim 0.050 mg and 0.100 mg patches, but not until week 3 for Esclim 0.025 mg. However, breast tenderness, endometrial hyperplasia, and abnormal bleeding all increased as the dose of estrogen increased.[24] A study of various doses of orally administered FemHRT in 219 postmenopausal women found similar results. Significant reductions in hot flash frequency occurred by week 2 in the highest-dose regimens (norethindrone acetate 1 mg/ethinyl estradiol 10 mcg), by week 3 in moderate doses (norethindrone acetate 1 mg/5 mcg ethinyl estradiol), and by week 5 for the lower doses (norethindrone acetate 0.5/ethinyl estradiol 2.5 mcg).[28]

The most effective alternatives to HRT for the relief of hot flashes are progestin-only regimens. Depo medroxyprogesterone acetate, megestrol acetate, and topical progesterone cream (although not wild yam creams) have all been shown to reduce hot flash severity and frequency by 80% to 90%.[26] Although wild yam and progesterone creams share similar properties, progesterone is a derivative of cholesterol and, therefore, readily bioavailable. In contrast, the human body is unable to metabolize wild yam cream, despite the similarities between the two compounds.[29] Although effective, progestin-only products have not been widely used due to concerns about safety. Use of these products may be associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic disease[30] and could theoretically increase the risk of breast cancer.[26,30] There is in vivo evidence that progestins induce a biphasic response; initial exposure results in a proliferative burst, but sustained exposure results in inhibition of the proliferation of breast tissue.[31] The relationship between progestins and breast cancer remains controversial.[31] A clear consensus on whether progestin contributes to breast cancer risk awaits the results of the ongoing arm of the WHI for women taking only estrogen.

Other older medications have historically been recommended for the relief of hot flashes, but they have side effect profiles that limit their use. For example, clonidine is minimally more effective than placebo but is associated with more adverse effects, most notably insomnia.[26] Belladonna/phenobarbital combinations were recommended in the 1970s and 1980s, but they appear to be minimally effective and potentially addictive.[26]

The newest drugs of interest are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which show great promise in reducing vasomotor symptoms. Effexor (Venlafaxine), Prozac (Fluoxetine), and Paxil (Paroxetine) have all been shown to significantly reduce hot flashes in randomized trials. Of these, Effexor and Paxil seem to provide the best relief and reduce vasomotor symptoms by 50% to 61%[32,33] and 62% to 67%, respectively.[34,35] These results were achieved by using dosage of Effexor 75 mg daily, Paxil 20 mg daily, and Paxil CR 12.5 mg to 25 mg daily. The largest study evaluating Effexor was a randomized, dose-seeking trial (of 37.5 mg, 75 mg, and 150 mg) in more than 200 women and found reductions of 37%, 61%, and 61%, respectively, in the incidence of hot flashes compared to a 24% reduction in the placebo group.[33] The largest study evaluating Paxil randomly assigned 56 women to receive placebo, 51 to receive Paxil CR 12.5 mg daily, and 58 to receive Paxil CR 25 mg daily. Hot flashes were reduced by 37% in the placebo group, 62% in the group receiving 12.5 mg, and 64% in the group receiving 25 mg.[35] Studies evaluating Prozac had less impressive results. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of 81 women evaluating the effectiveness of 20 mg of Prozac (Fluoxetine) found that women in the treatment arm had a 50% decrease in hot flash scores compared to 36% in the placebo arm.[36] Other SSRIs may be even less effective. A preliminary report of an ongoing study of Zoloft (Sertaline) shows that Zoloft seems to be no more effective than placebo.[37]

It should be noted that although these studies met many of the criteria needed to determine effectiveness (size of over 50, placebo-controlled, and randomized), participants were only followed for 1 month. On the basis of these studies, it appears that at least some of the SSRIs seem to be effective in relieving vasomotor symptoms in the short term and could be considered an option for women not interested in or able to use HRT. The exact extent of relief provided by the SSRIs over time, the dosage needed to achieve maximal benefit, and whether the impact varies by specific drug are not yet clear. The answers to these questions will have to wait until the conclusion of follow-up studies.

Other modalities, such as herbs and dietary supplements, seem to have marginal impact on hot flash relief at best. A randomized clinical trial of vitamin E[38] in 105 women showed that the treatment group had one less daily hot flash than the placebo group, whereas the studies on black cohosh and soy have been mixed -- with some trials showing improvement with the use of these products[39-42] and others no improvement.[43-46] Other approaches, such as applied relaxation,[47] appear effective but are based on small non-randomized studies.

Insomnia

HRT has long been thought to improve sleep by reducing the frequency and severity of hot flashes. A recent prospective double-blind crossover study of 63 postmenopausal women confirms these findings, but it also suggested that ERT improved the quality of sleep independently of the relief of vasomotor symptoms.[48] However, a follow-up study of 62 women undergoing sleep laboratory analysis demonstrated no significant differences in sleep latency, distribution of sleep states, sleep efficiency, or total sleep time in either the treatment arm receiving estrogen or in the placebo group. Therefore, it appears that ERT improves insomnia by minimizing nighttime arousal, not by changing the quality and quantity of sleep states or the ability to fall asleep.[18]

Women requesting help managing insomnia during the perimenopause could consider the use of herbs, dietary supplements, exercise, or the use of behavior modification. All of these approaches have been found helpful to various degrees for individuals experiencing primary insomnia but have not been studied specifically for women experiencing difficulty during the menopausal transition. Valerian and tryptophan have long been recommended as sleep aids.[49] Tryptophan was widely used as a dietary supplement until 1989 when the Food and Drug Administration banned its use after more than 1,500 individuals became ill following ingestion of contaminated supplements. 5-Hydrosytroptophan, a derivative of tryptophan, is available and has been studied for the treatment of depression but not insomnia. It is thought to be safer but should not be used by those taking SSRIs or monoamine oxidase inhibitors due to the risk of developing serotonin syndrome.[49] Valerian, made from the roots, rhizomes, and stolons of the plant, is available as a tea, extract, powder, or capsule. Valerian has been found to be safe and does not affect alertness, reaction time, or concentration. Recent sleep laboratory research seems to indicate that tryptophan depletion disrupts normal sleep architecture[50,51] and that the use of 270 mg/d to 600 mg/d of Valerian extract for 2 to 4 weeks improves insomnia.[49] However, larger studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of Valerian as a sleep aid. Other herbs, such as chamomile, passionflower, lemon balm, lavender, catnip, and skull cap, have been recommended for their sedative effects, but they have not been studied in controlled trials.[49]

Only a few research studies have evaluated the impact of exercise on insomnia, but the few studies that exist support the premise that exercise improves insomnia, primarily by increasing total sleep time and decreasing sleep latency. To maximize the benefit of exercise, individuals should be counseled that duration of exercise is more important than intensity and that exercise should occur 5 to 6 hours (minimum of 3 hours) before bedtime.[49]

The most effective non-pharmacologic treatments for insomnia are behavior modification therapies. These therapies aim to correct inappropriate sleep patterns by reserving time in bed for sleep, by establishing regular sleep and exercise patterns, and by encouraging lifestyle practices that promote effective sleep[49] (Table 2).

Genitourinary Symptoms

Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and pruritus are all commonly reported by peri- and postmenopausal women. These symptoms are all equally improved by any of the locally applied estrogen products, such as vaginal rings, creams, or tablets, and are the recommended HRT choices for vaginal complaints.[52] Although all locally applied HRT products appear to be equally effective, they are not all equally acceptable to patients. In addition, they vary according to their ability to stimulate the endometrium. In one study comparing 17-β estradiol 25-mcg vaginal tablets (Vagifem) to CEE cream 1.25 mg/d, both products produced similar improvements in vaginal atrophy. However, the use of the higher dose CEE cream was less acceptable to women and significantly more likely to lead to the development of proliferative endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia.[53] In clinical practice, many women use lower CEE cream doses than 1.25 mg and so may be less likely to develop hyperplasia.

Vaginal rings also seem to be more acceptable to women than cream. In a study comparing the ring and CEE 0.625-mg vaginal cream, the ring was rated "good" by 84% of users compared to 43% of cream users.[53] The ring also seems to cause less endometrial proliferation than CEE cream. Bachman reports that only 3.9% of ring users (compared to 13.3% of CEE cream users) had a positive progestogen challenge test. This challenge test, which indicates endometrial stimulation by estrogen, is positive if vaginal bleeding is induced after receiving 10 to 14 days of MPA or other progestin.[54]

The minimum number of doses of vaginal ERT products needed to provide relief from genitourinary symptoms is unclear. Studies use two different approaches to evaluate the effectiveness of HRT products, either changes in vaginal maturation index, which is obtained via a Papanicolaou smear or changes in symptoms such as pruritus, dyspareunia, and dryness. Higher doses of estrogen afford quicker and more complete relief and restore vaginal cytology to a premenopausal profile, but lower doses may be adequate (and safer with regard to endometrial cancer) for women with less pronounced symptoms. For example, a study of seven women documented significant relief of symptoms with the use of low levels of Estrace cream (estradiol).[55] The usual dose recommended by the manufacturer is 100 mcg/d to 400 mcg/d. However, doses of 10 mcg/d relieved more than 80% of symptoms without increasing serum levels of estrogen or causing endometrial hyperplasia.[55] Vaginal estradiol 2 mg rings, which release 7.5 mcg/d, also provide low-dose effective relief with minimal endometrial hyperplasia. In a study comparing dosages of 0.3, 0.625, 1.25, and 2.5 mg of CEE over 4 weeks, the lowest dose that restored vaginal cytology to premenopausal levels was 0.3 mg a day.[53] Doses of 1.25 mg/d were required in this study to achieve complete symptomatic relief.[53] However, as with oral products, it may be that given longer follow-up, lower doses may provide acceptable relief.

Other HRT routes may also improve vaginal symptoms but may be less effective. In the majority of studies, although oral doses as low as CEE 0.3 mg/d[27] and transdermal doses of 12.5 mcg/d[55] have shown improvement in vaginal maturation index, the impact of low doses on symptomatic relief has been mixed. In one study comparing transdermal estradiol doses of 50, 100, and 150 mcg/d, only the highest dose relieved vaginal irritation.[53] In contrast, a more recent study of 10 women using a very low dose estradiol patch (12.5 mcg/d) found both improved cytology and fewer complaints of vaginal dryness and irritation in patch users than in the placebo group.[55] The discrepancy between the findings of these various studies may be a result of their design. Many used different outcome measures, populations, sample sizes, and length of follow-up. This lack of standardization led the authors of one large recent metanalysis to conclude that the research to date is insufficient to establish clear clinical guidelines about the appropriate choice of products or duration of their use[52] and has led researchers to promote the use of standardized methodology to better evaluate symptom relief.[21,56]

Women seeking relief from vaginal dryness have other options available for use. Several studies have documented improvement in the maturation of the vaginal epithelium[57] or in symptoms[58,59] with the use of Replens equivalent to that provided by estrogen creams. Another randomized crossover trial of Replens found no differences between the placebo group (palm oil lubricant) and Replens. Both decreased vaginal dryness by 60%. Placebo lubricant improved dyspareunia scores by 40% compared to 60% for Replens.[60] It may be that the placebo used in this study has qualities similar enough to Replens to allow both products to provide relief, because clinical trials of other lubricants do not show the same positive effects seen with Replens. A double-blind, randomized, crossover trial of 93 peri- and postmenopausal women compared Replens and KY Jelly. Replens provided a longer duration of lubrication, a lower vaginal pH, and was preferred by more women (61% preferred Replens versus 25% KY Jelly).[53]

HRT use also seems to relieve some, but not all, urinary symptoms. Bachman[54] concludes that locally applied ERT products (estriol pessaries, CEE cream, estradiol vaginal rings, and estriol cream) all equally relieve symptoms of dysuria and urgency. The impact of HRT use on urinary incontinence is less clear and may vary by route of administration. Although older studies indicate that use of estrogen improves stress incontinence by up to 50%,[61,62] a recent randomized trial suggests that oral HRT may actually worsen stress incontinence. Research from the HERs study[63] of more than 1,500 women randomized to receive either 0.625 mg CEE/2.5 mg MPA or placebo indicate that the treatment group had significantly worsening urge and stress incontinence over the course of the 4-year study than that of the placebo group (odds ratio [OR]: 1.5; confidence interval [CI]: 1.26-1.82). The number of incontinent episodes increased by 0.7 per week in the hormone group and declined 0.1 per week in the placebo group.[63] In a review of 24 studies on HRT use and stress incontinence, Al-Badir concluded that symptomatic or clinical improvement was found only in nonrandomized studies.[64] However, a review of several randomized controlled trials of vaginal estrogen suggests improvement in urge and stress incontinence.[65] In a study of 10 postmenopausal women, Cicinelli et al.[66] found that placement of vaginal products in the outer third of the vagina increased blood flow dramatically to the periurethal vessels, whereas placement deep in the vagina, as recommended by manufacturers, resulted in significantly increased blood flow to the uterine arteries, but not those to the urethra. Therefore, some of the discrepancies in the results of the studies may be a result of differences not only in the type of HRT used (oral versus local) but also by placement of vaginal products (outer versus inner third of the vagina). Therefore, more randomized clinical trials may be warranted to determine whether oral or vaginal products, or neither, are helpful in the management of incontinence.

Women seeking relief from incontinence may find the use of behavioral techniques helpful. One randomized study of women receiving six weekly instructional sessions on bladder training and assigned a voiding schedule found that women in the treatment group had a 50% reduction in incontinent episodes compared to a 15% reduction in the placebo group.[67]

Maximizing Safety

Despite the risks elucidated by the WHI study, HRT use still has its place in the management of menopausal symptoms. No other method provides such consistent and complete relief of unwanted menopausal symptoms. However, to maximize the safety of HRT use, midwives should consider the following suggestions.

Use the lowest possible dose of estrogen needed for relief. Doses of oral and vaginal CEE as low as 0.3 mg have been shown to provide effective relief from hot flashes and vaginal discomfort. Transdermal doses of estradiol as low as 12.5 mcg also have been shown to provide relief. Lower-dose products are now widely available, including many patches (Vivelle 0.025, 0.0375; Climara 0.025; Esclim 0.025, 0.0375), and oral products, such as Premarin, Menest, and Estratab, come in 0.3 mg doses. In 2003, Wyeth Ayerst introduced Premarin 0.45 mg and Prempro 0.45/1.5 for a midrange dose that some women will require to relieve symptoms. However, women using low doses should be counseled to expect a delayed response, because it takes longer to achieve maximal benefit with low-dose regimens.

Consider adding a progestin if the patient on ultralow dose ERT regimens remains symptomatic. In one study,[27] adding MPA 1.5 mg to CEE 0.3 mg raised the effectiveness of this regimen in the relief of vasomotor symptoms to that afforded by standard doses (CEE 0.625 mg/MPA 2.5 mg). Although adding (or raising) progestin doses may be problematic, given the possible association of progestins with breast cancer, this dose of medroxyprogesterone acetate is substantially less than the standard dose. Because breast cancer may also be associated with estrogen use,[68] using the minimum dose of both estrogen and progestin needed to relieve symptoms is prudent and may help decrease the risk of developing breast cancer.

Use local products for vaginal and urinary complaints. Estrogen creams, rings, and suppositories are more effective than oral products and have minimum systemic absorption. Therefore, they may pose fewer systemic risks for stroke, breast cancer, and so forth and also may not require the addition of a progestin to prevent endometrial hyperplasia if low doses are used. Of the locally applied products, vaginal estradiol rings (Estring) and 17β-estradiol suppositories (Vagifem) seem to have the lowest systemic absorption and consequently may be less likely to be associated with the serious complications associated with HRT use.

Consider minimizing progestin exposure. Standard doses of continuous and sequential progestins (MPA 5 mg-10 mg for 10 to 14 days each month) with standard estrogen doses (CEE 0.625 mg) lead to very low rates of endometrial hyperplasia -- approximately 1%, which is similar to rates found in women not using any ERT or HRT products. Women using ERT *****ceive MPA 5 mg or 10 mg every 3 months have only slightly higher rates of hyperplasia (1.5%).[69] Women on lower-dose estrogen regimens (less than 0.625 mg) may be able to safely use progestins even less frequently. In one study of women receiving CEE 0.3 mg daily plus MPA 10 mg daily for 14 days every 6 months, the rate of endometrial hyperplasia was only 1.6%.[70] Therefore, use of quarterly or biyearly progestin schedules seems to be almost as effective at preventing endometrial hyperplasia as monthly or continuous regimens and may be safer (if progestins are found to increase the risk of breast cancer). Indeed, some authors now question whether progestin supplementation is necessary at all with low-dose estrogen regimens.[71] However, it should be noted that randomized controlled trials are needed before definitive recommendations can be given regarding what is the most appropriate progestin schedule or whether progestins are needed at all.

Consider short-term use. According to the results of the WHI, the risk of breast cancer does not seem to substantially increase until after 5 years of HRT use. Because menopausal symptoms abate for most women within 5 years of the onset of menopause, short-term use should provide relief without substantially raising risks of breast cancer.

Consider using alternative progestins. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions trial (PEPI), which looked at the impact of various HRT regimens on lipid profiles, found that CEE with cyclic micronized progesterone was associated with the best lipid profile of any of the combined regimens included in the study and closely approximated the improvements seen with CEE alone.[7] Therefore, it may be that micronized progesterone is cardio-neutral compared to Prempro, the HRT regimen used in the WHI trial. In addition, progestins, such as micronized progesterone and norethindrone acetate, seem to have better side effect profiles than MPA.[72,73] Women using these products report less breast tenderness and vaginal bleeding. Consequently, using progestins other than MPA may be safer and better tolerated by women requesting combined HRT products.

Combine approaches. Unfortunately, there is little research on whether combining different modalities (herbs, medications, and lifestyle changes) provides better relief than use of one method alone. Several studies seem to indicate that combining methods is more effective.[40,74] If future research substantiates this approach, doses of HRT may be able to be reduced, potentially increasing the safety of using HRT. Alternatively, using multiple non-HRT-based approaches may also provide acceptable relief.

Use alternative approaches. Of the options besides HRT, the SSRIs, especially Effexor and Paxil, seem to provide good relief from vasomotor symptoms. Replens appears to be an effective alternative for the treatment of vaginal dryness and dsypareunia, whereas behavioral interventions provide the best relief for urinary symptoms and insomnia. Studies of other alternative approaches are often small with significant design flaws such as insufficient follow-up, small sample sizes, and lack control for confounding variables. However, interventions such as dietary changes (adding vitamin E, black cohosh, or soy to the diet), although not likely to provide substantial relief based on current studies, may be effective adjunctive measures and are safe to use. Given the design flaws in many of these studies, midwives must use their clinical judgment until further research of sufficient size and quality is available to better guide clinical practice.

Conclusion

Although the WHI data demonstrate that HRT should not be used for prevention of chronic diseases, HRT is still the best treatment for relief of menopausal symptoms. Short-term use can be considered for women with severe symptoms because the absolute risks for HRT use are small. Midwives can help women find the best choice(s) from an array of options ranging from various estrogen and progestin preparations to alternative medications to lifestyle modifications. Women who avail themselves to some or all these options should be able to successfully manage many, if not all, of their menopausal symptoms.

CE Information

The print version of this article was originally certified for CE credit. For accreditation details, contact the publisher. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, published by Elsevier Inc. Corporate and editorial offices: The Curtis Center. Independence Square West, Philadelphia, PA 19106-3399.

Tables

Table 1. Risk of Selected Health Outcomes From the Use of HRT as Reported in the Womens' Health Initiative Hormone Replacement Therapy Trial[12]

Outcome Measure Relative Risk (CI)

(HRT vs. no HRT) Absolute Risk

(HRT vs. no HRT

in 10,000 women

over 1 year)

Invasive breast cancer 1.26 (1.00–1.59) 8 more women affected

Coronary heart disease 1.29 (1.02–1.63) 7 more women affected

Stroke 1.41 (1.07–1.85) 8 more women affected

Pulmonary embolism 2.13 (1.39–3.25) 8 more women affected

Hip fractures 0.66 (CI 0.45–0.98) 5 fewer women affected

Colorectal cancer 0.63 (CI 0.43–0.92) 6 fewer women affected

Reprinted with permission from Rousseau ME.[4]

Table 2. Appropriate Sleep Hygiene Measures

Use bed for sex and sleep only

Go to bed only when sleepy

Get up after 15 to 20 minutes if unable to fall asleep, return only when sleepy

Take no daytime naps

Maintain a consistent wake up time, no matter how much sleep obtained

Have no coffee or cigarette smoking 4 to 6 hours before bedtime

Have no more than one serving of alcohol consumed 2 hours or more before bedtime

Exercise no sooner than 3 hours before bedtime

Set a regular prebed routine

Eat no closer than 2 hours before bedtime

Turn your clock away so that you cannot see the time

Adapted from Larzelerle M.[49]

References

Brett K, Madans J. Use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: Estimates from a nationally representative cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:536-545.

Fletcher S, Colditz G. Failure of estrogen plus progestin therapy for prevention. JAMA 2002;288:366-367.

Austin P, Mamdani M, Tu K, Jaakkimainen L. Prescriptions for estrogen replacement therapy in Ontario before and after publication of the Women's Health Initiative Study. JAMA 2003;289:3241-3242.

Rousseau ME. Hormone replacement therapy: Short-term versus long-term use. J Midwifery Womens Health 2002;47:461-470.

Andersen LF, Gram J, Skouby SO, Jespersen J. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on hemostatic cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:283-289.

Kamali P, Muller T, Lang U, Clapp J. Cardiovascular responses of perimenopausal women to hormonal replacement therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:17-22.

The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial. JAMA 1995;273:199-208.

Mosca L, Manson JE, Sutherland SE, Langer R, Manolio T, Barrett-Connor EC. Cardiovascular disease in women: A statement for health care professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 1997;96:2468-2482.

Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg D, Herrington D, Riggs B. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA 1998;280:605-613.

Hulley S, Furberg C, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley J, Grady D, Haskell W, et al. Noncardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS 11). JAMA 2002;288:58-66.

Mosca L, Collins P, Herrington D, Mendelsohn M, Pasternak R, Robertson RM, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: A statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2001;104:499-503.

Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-333.

Grodstein F, Mason J, Stampfer M. Postmenopausal hormone use and secondary prevention of coronary events in the Nurse's Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2001;2001:1-8.

North American Menopause Society. Role of progestogen in hormone therapy for postmenopausal women: Position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2003;10:113-132.

Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy for primary prevention of chronic conditions: Recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:834-839.

Grady D. Postmenopausal hormones -- Therapy for symptoms only. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1835-1837.

Bachmann G. Vasomotor flushes in menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:S312-s316.

Polo-Kantola P, Errkola R, Irjala K. Effect of short-term transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on sleep: A randomized, double-blind crossover trial in post menopausal women. Fertil Steril 1999;71:873-880.

McNagny S. Prescribing hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:605-616.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hormone replacement therapy: ACOG Technical Bulletin Number 166-April 1992. Int J Gynecol Obstet 1993;41:194-202.

Sloan J, Loprinzi C, Novotny P, Barton D, Lavasseur B, Windschitl H. Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:4280-4290.

Many menopausal women using complementary therapies for symptoms. Anonymous. Reuters Medical News, 2000. [cited Nov 6, 2000]. Available from: http://womenshealth.medscape.com/reuters/prof/2000/10/10.3/2 0001027epid02.html.

Greendale G, Reboussin B, Hogan P, Barnabei V, Shumaker S, Johnson S, et al. Symptom relief and side effects of postmenopausal hormones: Results from the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Intervention Trial. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:982-988.

Utian W, Burry K, Archer D, Gallagher J, Boyett R, Guy M, et al. Efficacy and safety of low, standard, and high dosages of an estradiol transdermal system (Esclim) compared with placebo on vasomotor symptoms in highly symptomatic menopausal patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:71-79.

Nash H, Alvarez-Sanchez F, Mishell D, Fraser I, Maruo T, Harmon T. Estradiol-delivering vaginal rings for hormone replacement therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181:1400-1406.

Shanafelt T, Barton D, Adjei A, Loprinzi C. Pathophysiology and treatment of hot flashes. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:1207-1218.

Utian W, Shoupe D, Bachmann G, Pinkerton J, Pickar J. Relief of vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy with lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate. Fertil Steril 2001;75:1065-1079.

Speroff L, Symons J, Kempfer N, Rowan J, Investigators FS. The effect of varying low-dose combinations of norethindrone acetate and ethinyl estradiol (femhrt) on the frequency and intensity of vasomotor symptoms. Menopause 2000;7:383-390.

Gambrell D. Progesterone skin cream and measurements of absorption. Menopause 2003;10:1-5.

Loprinzi C, Michalak J, Quella S, O'Fallon J, Hatfield A, Nelimark R, et al. Megestrol acetate for the prevention of hot flashes. N Engl J Med 1994;331:347-352.

Eden J. Progestins and breast cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:1123-1131.

Loprinzi C, Pisansky T, Fonseca R, Sloan J, Zahasky K, Quella S, et al. Pilot evaluation of venlafaxine hydrochloride for the therapy of hot flashes in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2377-2381.

Loprinzi C, Kugler J, Sloan J, Mailliard J, LaVasseur B, Barton D, et al. Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;356:2059-2063.

Stearns V, Isaacs C, Rowland J, Crawford J, Ellis M, Kramer R, et al. A pilot trial assessing the efficacy of paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil®) in controlling hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol 2000;11:17-22.

Stearns V, Beebe K, Iyengar M, Dube E. Paroxetine controlled release in the treatment of menopausal hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2827-2834.

Loprinzi C, Sloan J, Perez E, Quella S, Stella P, Mailliard J, et al. Phase 3 evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1578-1583.

Stearns V, Hayes D. Cooling off hot flashes. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1436-1438.

Barton D, Loprinzi C, Quella S, Sloan J, Veeder M, Egner J, et al. Prospective evaluation of vitamin E for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:495-500.

Albertazzia P, Pansinia F, Bonaccorsia G, Zanottia L, Forinia E, De Aloysioa D. The effect of dietary soy supplementation on hot flushes. Obstet Gynecol 1998;91:6-11.

Scambia G, Mango D, Signorile P, Anselmi A, Palena C, Gallo D, et al. Clinical effects of a standardized soy extract in postmenopausal women: A pilot study. Menopause 2000;7:76-77.

Faure E, Chantre P, Mares P. Effects of a standardized soy extract on hot flushes: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Menopause 2002;9:329-334.

Taylor M. Botanicals: Medicines and menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2001;44:853-863.

St. Germain A, Peterson C, Robinson J, Alekel DL. Isoflavone-rich or isoflavone-poor soy protein does not reduce menopausal symptoms during 24 weeks of treatment. Menopause 2001;8:17-26.

Quella SK, Loprinzi CL, Barton DL, Knost JA, LaVasseur BI, Swan D, Krupp KR, Miller KD, Novotny PJ. Evaluation of soy phytoestrogens for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group Trial. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1068-1074.

Van Patten C, Olivotto I, Chambers G, Gelmon K, Hislop T, Templeton E, et al. Effect of soy phytoestrogens on hot flashes in postmenopausal women with breast cancer: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1449-1455.

Jacobson J, Troxel A, Evans J, Klaus L, Vahdat L, Kinne D, et al. Randomized trial of black cohosh for the treatment of hot flashes among women with a history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2739-2745.

Wijma K, Melin A, Nedstrand E, Hammar M. Treatment of menopausal symptoms with applied relaxation: A pilot study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1997;28:251-261.

Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Helenius H, Irjala K, Polo O. When does estrogen replacement therapy improve sleep quality?. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178:1002-1009.

Larzelere M, Wiseman P. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Prim Care Clin Office Pract 2002;29:339-360.

Arnulf I, Quintin P, Alvarez J, Vigil L, Touitou Y, Lebre A, et al. Mid-morning tryptophan depletion delays REM sleep onset in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;27:843-851.

Riemann D, Feige B, Hornyak M, Koch S, Hohagen F, Voderholzer U. The tryptophan depletion test: Impact on sleep in primary insomnia -- A pilot study. Psychiatry Res 2002;109:129-135.

Cardazo L, Bachmann G, McClish D, Fonda D, Birgerson L. Meta-analysis of estrogen therapy in the management of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women: Second Report of the Hormones and Urogenital Therapy Committee. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:722-727.

Willhite L, O'Connell MB. Urogenital atrophy: Prevention and treatment. Pharmacotherapy 2001;21:464-480.

Bachmann G. The estradiol vaginal ring -- A study of existing clinical data. Maturitas 1995;22:S21-s29.

Santen R, Pinkerton J, Conaway M, Roopka M, Wisniewshi L, Demers L, et al. Treatment of urogenital atrophy with low dose estradiol: Preliminary results. Menopause 2002;9:179-187.

McKenna S, Whalley D, Renck-Hooper U, Carlin S, Doward L. The development of a quality of life instrument for use with post-menopausal women with urogenital atrophy in the UK and Sweden. Qual Life Res 1999;8:393-398.

van der Laak J, de Bie L, de Leeuw H, de Wilde P, Hanselaar A. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: Cytomorphology versus computerised cytometry. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:446-451.

Bygdeman M, Swahn M. Replens versus dienoestrol cream in the symptomatic treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 1996;23:259-263.

Nachtigall L. Comparative study: Replens versus local estrogen in menopausal women. Fertil Steril 1994;61:178-180.

Loprinzi C, Abu-Ghazaleh S, Sloan J, van Haelst-Pisani C, Hammer A, Rowland K, et al. Phase 3 randomized double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy of a polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:969-973.

Wilson P, Faragher B, Butler B, Bullock D, Robinson E, Brown A. Treatment with oral peperazine oestrone sulphate for genuine stress incontinence in postmenopausal women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1987;94:568.

Bhatia N, Bergman A, Karram M. Effects of estrogen on urethral function in women with urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 1989;160:176.

Grady D, Brown J, Vittinghoff E, Applegate W, Varner E, Snyder T. Postmenopausal hormones and incontinence: The heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:116-120.

Al-Badr A, Ross S, Soroka D, Drutz H. What is the available evidence for hormone replacement therapy in women with stress urinary incontinence?. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2003;25:567-574.

Thom D, Brown J. Reproductive and hormonal risk factors for urinary incontinence in later life: A review of the clinical and epidemiologic literature. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:1411-1417.

Cicinelli E, Di Naro E, De Ziegleer D, Matteo M, Morgese S, Galantino P, et al. Placement of the vaginal 17 beta estradiol tablets in the inner or outer one third of the vagina affects the preferential delivery of 17 beta estradiol toward the uterus or periurethral areas, thereby modifying efficacy and endometrial safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:55-58.

Subak L, Quesenberry C, Posner S, Cattolica E, Soghikian K. The effect of behavioral therapy on urinary incontinence: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:72-78.

Chen C-l, Weiss N, Newcomb P, Barlow W, White E. Hormone replacement therapy in relation to breast cancer. JAMA 2002;287:734-741.

Doren M. Hormonal replacement regimens and bleeding. Maturitas 2000;34:S17-S23.

Ettinger B, Pressman A, Van Gessel A. Low-dosage esterified estrogens opposed by progestin at 6 month intervals. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:205-211.

Naftolin F, Silver D. Is progestogen supplementation of ERT really necessary?. Menopause 2002;9:1-2.

Mattox J, Shulman L. Combined oral hormone replacement therapy formulations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:S38-S46.

*******s J, Brizendine L. Comparison of physical and emotional side effects of progesterone or medroxyporgesterone in early postmenopausal women. Menopause 2002;9:253-263.

Ishiko O, Hirai K, Sumi T, Tatsuta I, Ogita S. Hormone replacement therapy plus pelvic floor muscle exercise for postmenopausal stress incontinence: A randomized controlled trial. J Reprod Med 2001;46:213-220.

Reprint Address

Address correspondence to Barbara Hackley, CNM, MS, 215 Riverside Drive, Fairfield, CT 06430. E-mail: [email protected]

Barbara Hackley, CNM, MS, graduated from the University of Michigan in 1976 with a BSN and from Columbia University with a MS in Nurse-Midwifery in 1981.

Mary Ellen Rousseau, CNM, MS, is an Associate Professor at the Yale School of Nursing where she teaches gynecology to midwifery and nurse practitioner students.

-------------------------------------------------------

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/540531_11 this is just small section 11 or 12 in this article...

Nonhormonal Therapy for Menopause

Alternative Therapies for Management of Vasomotor Symptoms in Menopause

History. Menopause is defined as the absence of menses for 12 consecutive months. Perimenopause is the transitional period between normal menses and menopause. Hot flashes have been reported in up to 70% of women undergoing natural menopause and in almost all women undergoing surgical menopause.[45] A prospective study of 436 women found that 31% experienced hot flashes during perimenopause, even before any changes occurred in menses.[46]

Hot Flashes. Hot flashes are the number one complaint of peri-menopausal and postmenopausal women. A hot flash can be described as a warm sensation that begins at the top of the head and progresses toward the feet, frequently followed by chills. A hot flash may last for a few seconds or for several minutes and may occur as frequently as every hour to several times per week.

Risk Factors. Modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for hot flashes should be evaluated. Modifiable factors that have been shown to increase the risk of hot flashes include cigarette smoking,[47,48] body mass index >30 kg/m2,[48,49] and lack of exercise[49] (LOE 2c). Nonmodifiable risk factors include maternal history, menopause younger than 52 years of age, and abrupt menopause—induced by a surgical procedure,[50] chemotherapy, or irradiation. Approximately 65% of patients with a history of breast cancer have hot flashes,[51] and adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen or tamoxifen plus chemotherapy is associated with substantial worsening of menopause-related symptoms.[52]

Differential Diagnosis. It is important to exclude other causes of hot flashes, as clinically indicated. The differential diagnosis may include hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, carcinoid, panic disorder, diabetes, and side effects to medications such as antiestrogens or selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Pathophysiologic Factors. The physiologic mechanism whereby a hot flash occurs is thought to be a result of elevated body temperature leading to cutaneous vasodilatation, which results in flushing and sweating in association with a subsequent decrease in temperature, chills, and potentially relief. One belief is that within the hypothalamic thermoregulatory zone there is an interthreshold zone, defined as the threshold between sweating and shivering. Available evidence indicates that, after menopause, this interthreshold zone becomes narrowed.[53] Proposed triggers for this change in interthreshold zone include serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), norepinephrine, and estrogen deprivation. The estrogen effect on hot flashes is thought to be attributable to withdrawal of estrogen rather than decreased estrogen levels.[54]

Therapeutic Options

Because of the prevalence of hot flashes during the perimenopausal and postmenopausal period and the risks, controversies, and fears surrounding the use of estrogen therapy, various alternative therapies for managing these symptoms have been sought. An important fact to know is that, in most studies, interventions for menopausal symptoms have a 20% to 30% placebo response rate within 4 weeks after initiation of treatment, with some randomized trials having more than a 50% placebo response rate.[55] In most women, treatment of hot flashes can be discontinued within 1 year, but about a third of the menopausal women have symptoms for up to 5 years (10% of whom have symptoms for up to 15 years). In light of the high placebo response rate and the natural regression of symptoms over time in most women, double-blind RCTs are needed to evaluate the efficacy of each therapeutic option appropriately. Additionally, because of the varied duration of time these treatments are used, both the short-term and long-term effects must be properly evaluated. Of note, other than estrogen, no therapy has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of hot flashes in women. Estrogen remains the most studied and most effective therapy for vasomotor symptoms attributable to menopause. No RCTs comparing estrogen and other pharmacologic agents have been published. The level of evidence for each therapeutic intervention is presented in the subsequent material.

Lifestyle Alterations

Lifestyle changes designed to maintain a cool environment and aid heat dissipation may help with mild to moderate symptoms. The use of fans, air conditioning, and light cotton clothing may be helpful. Relaxation therapy may also be beneficial in some patients, although RCTs are needed for accurate assessment (LOE 3).

Prescription Medications

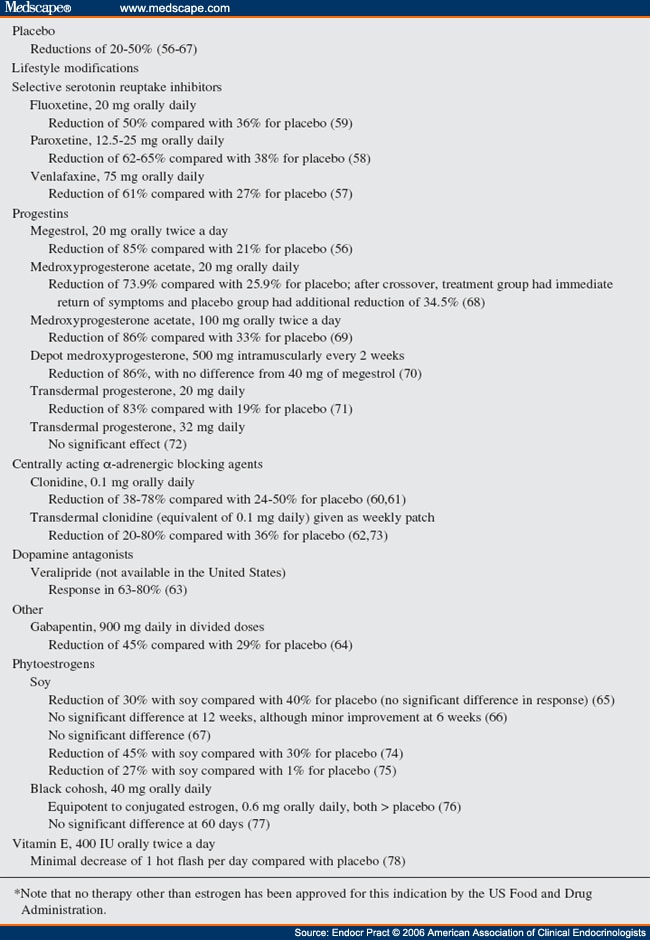

A summary of the various agents and the related published studies[56-78] is presented in Table 4 . As previously mentioned, no therapy other than estrogen has been approved by the FDA for treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

Antidepressant. The most studied medications in the antidepressant class include venlafaxine, paroxetine, and fluoxetine. Venlafaxine is both a serotonin and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. There have been 3 published RCTs in which these medications were used[57-59] (LOE 2). Side effects of these agents may include nausea, dry mouth, insomnia, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and gastrointestinal disturbances.

Clonidine. Clonidine is a central α2-adrenergic agonist and can be given orally or transdermally. A summary of results of trials that used clonidine preparations is shown in Table 4 [60-62,73] (LOE 2). Side effects, including dry mouth, postural hypotension, fatigue, and constipation, often limit the use of this medication.

Gabapentin. Gabapentin is an analogue of γ-aminobutyric acid and has an unknown mechanism of action. It is approved by the FDA for treatment of seizure disorders but has also been used to treat neuropathic pain. A small RCT[64] has demonstrated significant reductions in hot flashes ( Table 4 ), but larger trials are needed to study long-term efficacy and safety (LOE 2). Side effects may include fatigue, dizziness, and peripheral edema.

Progesterone and Progestins. Oral, intramuscular, and topical formulations of progestins have been used in the treatment of hot flashes. There have been 3 RCTs of orally administered progesterone[56,68,69] and 1 RCT of oral versus intramuscular administration of progesterone[70] ( Table 4 ) (LOE 2). Although these studies showed effectiveness in reducing hot flashes, the associated side effects, including withdrawal bleeding and weight gain, often limit the use of this medication.

Progesterone cream is classified as a supplement; therefore, it can be purchased without a prescription, and its contents are neither standardized nor regulated. Progesterone cream is derived from a plant precursor sterol, which in its unaltered or "natural" form is unable to be converted to progesterone by the human body. Commercial preparations of progesterone creams vary widely and may contain an unaltered, unusable form of progesterone or a variant that has been derived from plant sterols but modified in the laboratory to a form that can be utilized by the body.

Two RCTs of transdermal progesterone have been reported in the literature,[71,72] and these studies yielded conflicting results ( Table 4 ) (LOE 2c). Because of the paucity of data and the variability of these preparations, in addition to possible systemic effects, progesterone creams should not be recommended for the treatment of hot flashes.

Over-the-Counter Preparations

I***** the US Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act that defined dietary supplements as a separate regulatory category and outlined ways in which information about supplements could be advertised. It is important to be aware that this act does not require scientific evidence demonstrating safety or efficacy of supplements, and it does not regulate or require standardization of the manufacturing of supplements. Moreover, demonstration of harm from a supplement must be reported before the FDA will intervene or regulate that supplement. Despite these loose regulations and the intended benefits, supplements have the potential for interaction with other medications and medical conditions as well as the potential to cause harm.

In 1998, alternative medicine visits by patients outnumbered visits to conventional primary physicians. Seventy percent of these visits were never discussed with the primary physician. In 44% of such visits, the patients were 50 to 64 years old.[79] In one study, predictive factors for use of alternative care included higher education and chronic medical problems.[80] Some third-party carriers have begun providing coverage for alternative therapies (albeit at a premium). One survey of 100 post-menopausal women at a San Francisco health conference found that women who used dietary supplements for relief of menopausal symptoms had the highest perceived quality of life, felt most in control of their symptoms, and had a sense of empowerment.[81] In general, women are now living a third of their lives after menopause, and in light of the trend of increasing use of alternative medical therapies, the use of supplements for the management of hot flashes is likely to increase.

Phytoestrogens. Phytoestrogens, which can be subclassified as shown in Figure 1, are sterol molecules produced by plants with weak estrogenic activity. They are similar in structure to human estrogens and have been shown to interact and have estrogenlike activity with the estrogen receptor (greater activity at the beta receptor).[82] Plant sterols are used as a precursor for biosynthetic production of mass manufactured pharmaceutical-grade sterols.

Figure 1. (click image to zoom)

Subclassification of phytoestrogens, plant sources of weak estrogenic activity.

Isoflavones, a type of phytoestrogen, have been investigated in the treatment of hot flashes because women in Asia, whose diets characteristically contain 40 to 80 mg of isoflavones daily (in comparison with a typical American diet that contains <3 mg daily), have low rates of hot flashes.[83] Consumption of 1 g of soy yields between 1.2 and 1.7 mg of isoflavones. Because of the large amount of soy that must be consumed to achieve an intake of isoflavones that is typical of an Asian diet, a market for isoflavone concentrates (a nutraceutical) has developed.

Multiple RCTs examining the effects of soy or isoflavone consumption on the reduction of hot flashes have yielded inconsistent results[65-67,74,75] ( Table 4 ) (LOE 2).

Some studies of the effects of soy on hot flashes have examined raw soy consumption, whereas others have examined the effects of consumption of isoflavones. In addition, different amounts and formulations of these products were used in the various studies; thus, comparisons between studies are difficult. Isoflavones can be broken down to form daidzein, which can be further metabolized by intestinal bacteria into equol—a stable compound with estrogenic activity.[84,85] Only 30% to 50% of adults are able to excrete equol after a soy food challenge,[86] and differences in the ability to metabolize soy may explain variations in the response to soy treatment.

If women are interested in using soy, the average amount of isoflavones studied has been 40 to 80 mg daily for up to 6 months. It may take several weeks for any effect to occur, and women should be encouraged to use whole food sources, rather than supplements, because of the risk of overdosage and the lack of known long-term effects with use of isoflavone supplements. Women should be counseled that data regarding estrogenic effects of soy have been inconclusive; therefore, women with a personal or strong family history of hormone-dependent cancers (breast, uterine, or ovarian) or thromboembolic or cardiovascular events should not use soy-based therapies (grade D). Some evidence has indicated that soy can stimulate estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells in vitro.[86] Of note, a recent double-blind RCT of use of soy protein in older postmenopausal women did not yield differences in cognitive function, bone mineral density, or plasma lipids.[87] Long-term randomized controlled safety and efficacy studies in postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms are needed.

Black Cohosh. In Germany, black cohosh has been used for many years in the treatment of hot flashes. Most studies of black cohosh have used a commercial preparation, "Remifemin," which is reported to contain 1 mg of triterpene glycoside, calculated as 27-deoxyactein in each 20-mg tablet.

There are 3 published randomized, placebo-controlled trials of black cohosh—2 in the English-language literature[76,77] (LOE 2) and 1 in German[88]—which yielded inconsistent results. Although this therapy is thought to be generally safe, there have been rare case reports of hepatitis associated with preparations containing black cohosh.[89] Of importance, no safety trials of black cohosh have been conducted for longer than 6 months. Package labeling generally recommends use for no more than a 6-month period.

Vitamin E. The use of vitamin E for reduction of hot flashes in patients with a history of breast cancer has been reported in one randomized, placebo-controlled trial[78] ( Table 4 ) (LOE 2). At the conclusion of that study, there was no difference in results between vitamin E and placebo.

Vitamin E is considered relatively safe. In a review of studies of vitamin E, no adverse effects had been reported with dosages of 800 IU of vitamin E daily and even higher doses in some studies.[90,91] Evaluation of data from the WHI study indicated that 600 IU of natural-sou

Jamie Ellis RN MS NPP

100cm proximal Lap RNY 10/9/02 Dr. Singh Albany, NY

320(preop)/163(lowest)/185(current) 5'9'' (lost 45# before surgery)

Plastics 6/9/04 & 11/11/2005 Dr. King www.albanyplasticsurgeons.com

http://www.obesityhelp.com/member/jamiecatlady5/

"Being happy doesn't mean everything's perfect, it just means you've decided to see beyond the imperfections!"

. I'm going to be calling my GYN for a follow up visit since I just started on the patch

. I'm going to be calling my GYN for a follow up visit since I just started on the patch . My GYN actually attended a seminar for medical staff with my Bariatric Surgeon within the last few months.

. My GYN actually attended a seminar for medical staff with my Bariatric Surgeon within the last few months. Aganin thank you for your feedback. I just wanted to be a bit more informed when I see the doctor again.

I hope you get some relief and soon!

My cousin swears by eating tofu. She insists that it helps the with her night sweats...hey, it can't hurt to try, right?

Good luck and hopefully, I'll see you tomorrow at the LIPO meeting!

ME:)

To visit LIPO (Long Island Post Ops) bariatric support group website click here: www.liponation.org

"WLS is a journey, not a destination (don't get comfortable) ... it's a road that we must travel daily to succeed". Faith Thomas

visit my blog at theessenceofmaryellen.com/