How is WLS a tool?

Person1: You should lose weight before surgery so that surgery is easier and so that the adjustments are easier afterward.

Person2: You will lose 60% of your excess weight owing purely to surgery alone.

Person3: WLS is not a guarantee of weight loss. It is a tool.

So here's my pea-brained confusion.

I've been trying to lose weight for a long time. Tried harder since January while prepping for WLS. Last week tried to be very careful, felt very at peace with food choices, exercise and all. Gained 1. (Don't say it's muscle.)

So If I lose *Nothing before surgery*, Am I qualified for the tool? In a perfect world, I'd have the surgery, I'd drop the weight, I'd use the reduced appetite to change habits and increase exercise and that would lead to new habits and lifestyle that were healthier. ( Right now, I'm kind of restricted in movement because of my arthritis -- losing weight will help.)

So, is that how one uses WLS as a tool? From a place of unsuccess on the scales to a place of successful lifestyle changes? Using reduced intake as a time to do the head work for real? I gather that the usefulness of surgery goes down with time as the pouch heals and sometimes enlarges.

The last thing I want is to have this surgery and then be unsuccessful at losing weight and becoming more active.

edited to add -

#1. Some doctors & centers will require a patient to loose “X" amt of #s pre op. when a patient is required to loose it helps show that the person is motivated to change their life style & to see if they can follow the instructions that they are given because they will have specific guidelines to follow PO.

#1. Adjustments apply to the lapband WLS, not RNY Or are you referring to life style changes? Keep in mind that it takes at least 3 full months to put into play a life style change. It is not easy but the sooner you start putting them into practice the sooner you can benefit from them.

#1. it is easier on the patient to have lost some weight beforehand due to the shrinking of the liver (it will then be easier for the surgeon to get around if the surgery is done laproscopically). It also get the patient on/off the table faster & they are under anesthesia for less time. your doctor can tell you about all the risks.

#2. 60% is the statistics for the amount of weight a person can possibly loose with surgery, in this case RNY. The patient can loose more but it is up to them. they must be motivated to do it & keep it off. Both Dave and I have lost over 80% of our excess #s.

#3. absolutely the truth – you will be given a “tool" with the smaller stomach pouch & bypass for the malabsorbtion of calories. It is up to the patient to use it wisely & to not abuse it. No over eating to stretch the pouch & stoma, no drinking of your calories (sugar & alcohol) and eat according to your doctor’s guidelines . . .

Not loosing weight does not disqualify you from having WLS. I am not sure where you came up with that thought process. Yes, as you loose weight you should gain mobility, this individual to each patient. Using your WLS tool correctly & with life style changes of eating healthy food will help you see the scale #s go down. Each person brings their own baggage to the table & you have to change your own mindset. Remember – the doctor does surgery on your stomach not your brain, you have to change your brain.

Where did you come up with – “I gather that the usefulness of surgery goes down with time as the pouch heals and sometimes enlarges". It is up to you to make sure that the usefulness of surgery does not do down with time. eat correctly, slowly (letting your brain tell you that you are full) and not huge meals. Do not drink with your meals/snacks. The pouch is created out of the most upper section of the stomach with is an area that does not stretch that much. It can stretch slightly but it is the stoma (opening out of the pouch to the intestines) that can be stretch and let you eat copious amount of food. This comes from over eating time after time, after time . . . it is all up to you.

Everyone has had the same fear as you put in your last sentence. Its is up to you to make it a successful journey.

Open RNY May 7

260/155/140

I actually gained weight on my 6 month diet before surgery.

That shows that the typical diet doesn't work or only results in short term weight loss. Most of the time, we adhere to a very strict diet to lose weight which is not a normal eating pattern. Lose the weight.

That shows that the typical diet doesn't work or only results in short term weight loss. Most of the time, we adhere to a very strict diet to lose weight which is not a normal eating pattern. Lose the weight.  jump for joy, and resume our old eating habits and gradually gain back the lost weight and a few more pounds. Sound familiar?

jump for joy, and resume our old eating habits and gradually gain back the lost weight and a few more pounds. Sound familiar? Well, I did the 2 week liquid diet for my presurgery diet and I lost 40 pounds!

Did I ever cheat? Absolutely not! Have I cheated on other diets -- Uhm, yes.

Did I ever cheat? Absolutely not! Have I cheated on other diets -- Uhm, yes.

After surgery, you have this tiny pouch that cannot hold more than 2 ounces of food. Go get a measuring cup and measure 2 ounces of food. That is nothing. I made sugar free jello in a container the size of a shot glass and could only eat half of it and be stufffed! When have you ever eaten that quantity of food and felt full? The fullness of a thanksgiving meal? Never.

After surgery, you are reintroducing foods, just like you reintroduce foods to a baby -- gradually. You are learning new eating habits and hopefully these eating habits will stick with you for life.

Now here is where the tool can fail.

1. You can overeat, ignoring all signals of fullness and eventually stretch out your pouch so that it holds more food. It will naturally stretch some but how much depends on whether you drink with meals, and how much food you consume at one time.

2. You do have to make wise food choices. Although I love ice cream, I do not have traditional ice cream. I make a protein ice cream that allows me to get my protein and does not have the regular calories that traditional ice cream has. Yes, I probably could eat regular ice cream but with its fat and sugar content and high calories and ease of going down, I could really overeat and consume quite a few calories. The same with candy, chips etc.

3. One of the things the tool helps you with is learning to identify head hunger vs real hunger. Sometimes I will think I am hungry when it really is just a craving for something. By learning better food choices, I have learned to make better decisions. (I should have invested in the popsicle company because I think I could eat my weight in sugar free popsicles.

)

)4. Our tool is what we make of it. It works great the first 12 to 18 months during a "honeymoon" period in which you could probably eat anything and still lose weight. But if you choose to eat anything and dont learn new habits, and continue those habits, you will fail the tool and it wont work for you. The tool is always there for us to use. We have to use it wisely.

Sorry for the overly long answer. I always have been long winded.

Cat Lady

Cat Lady

First, one caution, if you have arthritis, be sure and ask your doc about taking pain medicine for the rest of your life with the RNY. NSAIDs are off-limits for your pouch. I have arthritis in my knees, so that, long-term weight loss rates, lifestyle preferences and diabetes resolution, influenced MY surgery choice.

If you've been truly trying to lose weight for a long time, doing the old "exercise and diet" BS and it hasn't worked, you probably need a surgery that will actually affect the way your body metabolizes food. That would rule out the VSG or band (which are purely restrictive). I would say failure to lose weight on that dumb diet is a good sign your body NEEDS a metabolic WLS.

With the RNY, it seems that weight regain is more than the pouch enlarging. It's the malabsorption naturally lessening at about 18-24 months, as the villi adapt and start absorbing more. Fairly soon after you heal, your absorption starts to increase, making more of what you eat to be available for storage and aargh--weight regain.

That's why establishing portion control, low-fat/low-carb diets and exercise early is important for the RNY surgery. You have to maximize that weight loss window and establish good habits early so that you can go the distance. There are a few people on the Main Board and on this board who have lost weight with a RNY and kept it off for a few years, so it can be done. I would listen to their wisdom.

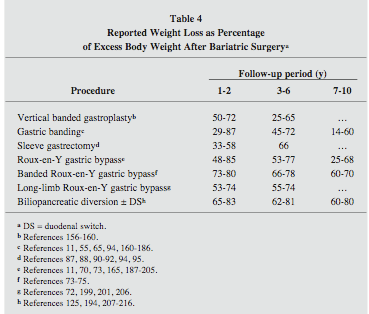

As to weight loss rates, I only concern myself with long-term weight loss, as I think all of the 4 available surgeries today will help us lose weight. Check out the AACE/TOS/ASMBS (Vol. 14 - July/August 2008). On page 10 there is a table of Reported Weight Loss as Percentage of Excess Body Weight after Bariatric Surgery as far as 7-10 years out.

Oh, and by the way, I GAINED weight on my 6-month diet. So far it hasn't held me back in my quest to lose and keep off nearly 200 pounds!

Best of luck to you!

Nicolle

I had the kick-butt duodenal switch (DS)!

HW: 344 lbs CW: 150 lbs

Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea GONE!

Nicole, do you have documentation or any studies for the info that you have posted regarding the villi? Because yesterday I sent an email to the nurse at Dr R's office regarding the info that you mentioned above and she said to me that she has never heard of this fact before. Now she is a certified bariatric nurse with many years in the field of bariatrics. She was with Dr R's office when I had my surgery in 2003 and before that also. She has never heard of any "time frame" for the malabsorbtion to be at its optimum. The bypass portion of the surgery was designed just for that "malabsorbtion" and restriction with the smaller stomach pouch and your body does not "adjust" and start absorbing again. Naturally it is crucial that the individual makes and maintains the necessary life style changes - that goes without saying.

Barb, the nurse and myself would be interested in scientific documentation regarding what you have posted.

Respectfully,

Chris

Open RNY May 7

260/155/140

Hi! Getting back on my feet over here--sorry for the "day" delay in response.

This is so weird to hear you say because every RNY surgeon I have met and seen present has acknowledged the intestine's hypertrophic response as a factor in weight regain after gastric bypass.

This includes locals such as Dr. Nagle at Northwestern, Dr. Cahill at Little Company and Dr. Frantizides in the burbs and nationally-known ones such as Garth Davis. They have all varied on their timeframes, as it really is as individual as can be, but they have generally agreed on the middle range of 18-24 months for intestinal absorption to increase. Their anecdotal experience with their patients bear this out, thus their repeated cautions to patients to maximize their early "weight loss window" and "develop good habits."

Plenty of research exists that proves intestinal adaptation/increase of absorption exists. Much of the research has been done to benefit people with short-gut (or short-bowel) syndrome and people with celiac disease. In THOSE patients, they are actually trying to get them to reduce malnutrition (i.e. absorb MORE nutrients and calories) from the existing intestine and in some cases, gain weight, versus what WE are trying to accomplish (maintaining weight loss while increasing nutrient absorption for the long-term). But now researchers are turning to this for obesity issues and vice versa.

Humans are highly adaptive and our bodies will "do what it takes" to try and stay alive, including become more absorptive when we "lose" part of our bowel to illness, injury, disease or surgery. It's a complex process that scientists are trying to understand, involving peptides, hormone signaling and other factors, INCLUDING location of the cuts made. The DS and RNY "cuts" are in different locations, so each has different results, some good, some bad.

Here are some of the most helpful articles you may want to send along to your surgeon's bariatric nurse for review.

1) General info on intestinal adaption in humans after surgery

http://www.springer

2) University of Chicago surgeons/researchers who say:

Intestinal adaptation

Another phenomenon that is poorly understood, particularly

in the context of malabsorptive bariatric surgery, is

that of intestinal adaptation. It is well recognized that the

absorptive capacity of the small bowel far exceeds its need.

Indeed, most carbohydrate, protein, and water-soluble

vitamin absorption takes place in the proximal 100–200 cm

jejunum, whereas fat absorption is distributed over a

broader length of the small bowel, dependent on the

amount of fat ingested [30]. In contrast, bile salt and B12

absorption is limited to specific carrier-mediated mechanisms

in the ileum. Additionally, the ileum is the major site

of fluid reabsorption, which takes place due to tighter

epithelial intercellular junctions (reducing water and

sodium fluxes by a factor of nine and two, respectively

[31, 32]) and aldosterone-mediated sodium absorption.

Indeed, despite the greater structural and functional

absorptive surface of the jejunum, in experimental models

as well as clinical observations, significant resection of the

ileum is not as well-tolerated as equivalent jejunal resection

and has a higher likelihood of resulting in short bowel

syndrome. The greater adaptability of the ileum is manifested

by both structural changes (hypertrophy and hyperplasia)

and functional changes (reduced epithelial

permeability, slower transit times, bile salt absorption)

compared with jejunum [33], and this difference in adaptive

ability is exploited with the preferential use of ileum in

small bowel transplantation [17]. Adaptation is a gradual

process, taking place over a period of 12–24 months, which

interestingly (and perhaps not coincidentally) corresponds

to the typical duration of active weight loss after malabsorptive

bariatric procedures. Indeed, in this setting, the

structural and functional changes associated with the

achievement of ileal adaptation may function as a ‘‘weightloss

brake.’’

www.springerlink.com/content/4655j02l571g5gq0/fulltext.pdf

3) Characterization of weight loss and weight regain mechanisms after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats

http://ajpregu.

4)

Gut hypertrophy after gastric bypass is associated with increased glucagon-like peptide 2 and intestinal crypt cell proliferation.

Annals of Surgery, July 2010

Department of Metabolic Medicine, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Campus, London, United Kingdom.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: We aimed to determine changes in crypt cell proliferation and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) in rodents and man after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). SUMMARY OF BACKGROUND DATA: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass results in sustained weight loss and reduced appetite with only mild gastrointestinal side effects. Glucagon-like peptide-2 released from intestinal l-cells after nutrient intake stimulates intestinal crypt cell proliferation and mitigates the effects of gut injury. METHODS: Wistar rats underwent either RYGB (n = 6) or sham procedure (n = 6) and plasma GLP-2, GLP-1, and gut hormone peptide YY (PYY) were measured after 23 days. Biopsies from the terminal ileum were stained using the antibody to Ki67, which detects cyclins and hence demonstrates cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle. The total number of cells, number of mitosis, and number of labeled cells per crypt were counted. Obese patients (n = 6) undergoing RYGB were evaluated following a 420 kcal meal preoperatively, and 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months later for responses in l-cell products such as GLP-2, GLP-1, total PYY, and PYY3-36. RESULTS: Rat GLP-2 levels after RYGB were elevated 91% above sham animals (P = 0.02). At necropsy, mitotic rate (P < 0.001) and cells positive for the antibody Ki67 (P < 0.001) were increased, indicating crypt cell proliferation. Human GLP-2 after RYGB reached a peak at 6 months of 168% (P < 0.01) above preoperative values. Area under the curve for GLP-1 (P < 0.0001), total PYY (P < 0.01), and PYY3-36 (P < 0.05) responses increased progressively over 24 months. CONCLUSIONS: RYGB leads to increased GLP-2 and mucosal crypt cell proliferation. Other gut hormones from l-cells remain elevated for at least 2 years in humans. These findings may account for the restoration of the absorptive surface area of the gut, which limits malabsorption and contributes to the long-term weight loss after RYGB.

5)http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20438940

J Pediatr Surg. 2010 May;45(5):987-95.

The influence of nutrients, biliary-pancreatic secretions, and systemic trophic hormones on intestinal adaptation in a Roux-en-Y bypass model.

Taqi E, Wallace LE, de Heuvel E, Chelikani PK, Zheng H, Berthoud HR, Holst JJ, Sigalet DL.

Faculty of Medicine, Division of Pediatric General Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada AB T3B 6A8.

Abstract

PURPOSE: The signals that govern the upregulation of nutrient absorption (adaptation) after intestinal resection are not well understood. A Gastric Roux-en-Y bypass (GRYB) model was used to isolate the relative contributions of direct mucosal stimulation by nutrients, biliary-pancreatic secretions, and systemic enteric hormones on intestinal adaptation in short bowel syndrome. METHODS: Male rats (350-400 g; n = 8/group) underwent sham or GRYB with pair feeding and were observed for 14 days. Weight and serum hormonal levels (glucagon-like peptide-2 [GLP-2], PYY) were quantified. Adaptation was assessed by intestinal morphology and crypt cell kinetics in each intestinal limb of the bypass and the equivalent points in the sham intestine. Mucosal growth factors and expression of transporter proteins were measured in each limb of the model. RESULTS: The GRYB animals lost weight compared to controls and exhibited significant adaptive changes with increased bowel width, villus height, crypt depth, and proliferation indices in the alimentary and common intestinal limbs. Although the biliary limb did not adapt at the mucosa, it did show an increased bowel width and crypt cell proliferation rate. The bypass animals had elevated levels of systemic PYY and GLP-2. At the mucosal level, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) increased in all limbs of the bypass animals, whereas keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) had variable responses. The expression of the passive transporter of glucose, GLUT-2, expression was increased, whereas GLUT-5 was unchanged in all limbs of the bypass groups. Expression of the active mucosal transporter of glucose, SGLT-1 was decreased in the alimentary limb. CONCLUSIONS: Adaptation occurred maximally in intestinal segments stimulated by nutrients. Partial adaptation in the biliary limb may reflect the effects of systemic hormones. Mucosal content of IGF-1, bFGF, and EGF appear to be stimulated by systemic hormones, potentially GLP-2, whereas KGF may be locally regulated. Further studies to examine the relationships between the factors controlling nutrient-induced adaptation are suggested.

Respectfully,

Nicolle

I had the kick-butt duodenal switch (DS)!

HW: 344 lbs CW: 150 lbs

Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea GONE!

I have not had a chance to read through all that you wrote but I will do that in the next few days. I am also going to cut and paste what you entered and e-mail it to Barb and Dr R and let them read through the info.

Open RNY May 7

260/155/140

Found another recent article that talks about intestinal adaptation after surgery. Villi growth, in particular.

Nicolle

--------------------------------------------------

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20595624

Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010 Jul 1. [Epub ahead of print]

Intestinal adaptation after ileal interposition surgery increases bile acid recycling and protects against obesity related co-morbidities.

1Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Ctr, Univ Cincinnatti.Abstract

Objective: Surgical interposition of distal ileum into the proximal jejunum is a bariatric procedure that improves the metabolic syndrome. Changes in intestinal and hepatic physiology after Ileal Interposition (transposition) Surgery (IIS) are not well understood. Our aim was to elucidate the adaptation of the interposed ileum, which we hypothesized, would lead to early bile acid reabsorption in the interposed ileum, thus short circuiting enterohepatic bile acid recycling to more proximal bowel segments. Design: Rats with diet-induced-obesity were randomized to IIS, with 10-cm of ileum repositioned distal to the duodenum, or sham surgery. A sub-group of sham rats was pair-fed to IIS rats. Physiologic parameters were measured until 6 weeks post-surgery. Results: IIS rats ate less and lost more weight for the first 2 weeks post-surgery. At study completion body weights were not different but IIS rats had reversed components of the metabolic syndrome. The interposed ileal segment adapted to a more jejunum-like villi length, mucosal surface area and GATA4/ILBP mRNA. The interposed segment retained capacity for bile acid reabsorption and anorectic hormone secretion with presence of ASBT and GLP-1 positive cells in the villi. IIS rats had reduced primary bile acid levels in the proximal intestinal tract and higher primary bile acid levels in the serum suggesting an early and efficient reabsorption of primary bile acids. IIS rats also had increased taurine and glycine-conjugated serum bile acids and reduced fecal bile acid loss. There was decreased hepatic Cyp27A1 mRNA with no changes in hepatic FXR, SHP or NTCP expression. Conclusions: IIS protects against the metabolic syndrome through short-circuiting enterohepatic bile acid recycling. There is early reabsorption of primary bile acids despite selective jejunization of the interposed ileal segment. Changes in serum bile acids or bile acid enterohepatic recycling may mediate the metabolic benefits seen after bariatric surgery.

I had the kick-butt duodenal switch (DS)!

HW: 344 lbs CW: 150 lbs

Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea GONE!